Gene editing extends lifespan in mouse model of prion disease

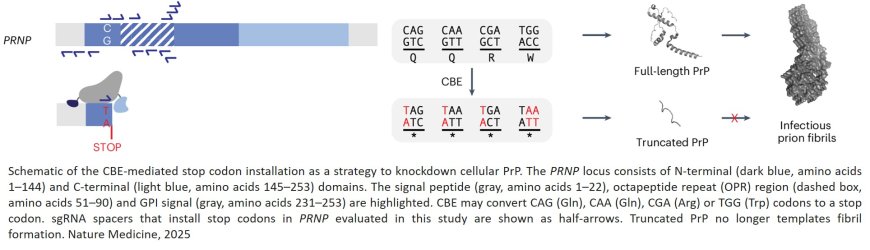

Researchers have developed a gene-editing treatment for prion disease that extends lifespan by about 50 percent in a mouse model of the fatal neurodegenerative condition. The treatment, which uses base editing to make a single-letter change in DNA, reduced levels of the disease-causing prion protein in the brain by as much as 60 percent.

There is currently no cure for prion disease, and the new approach could be an important step towards treatments that prevent the disease or slow its progression in patients who have already developed symptoms. A base-editing approach could also likely be a one-time treatment for all prion disease patients regardless of the genetic mutation causing their disease.

The work is the first demonstration that lowering levels of the prion protein improves lifespan in animals that have been infected with a human version of the protein. The findings appear in Nature Medicine.

“As a patient scientist, I think often about how lucky we are to be coming at this problem now,” said the author. “When I received my genetic test report in 2011, the world had never heard of base editing. It’s a huge privilege to have the opportunity to point these powerful new tools at our disease.”

“It’s been incredible to merge our disease models with this gene-editing technology,” another author said.

“Prion disease has a lot of different origins — some are genetic, some occur spontaneously, and others stem from infections — but we believe this base editing strategy can be applied to all of these forms of prion disease,” another author said. “This has the potential to be a really promising strategy.”

The authors knew from studying population databases such as the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) that R37X, a naturally occurring mutation in the prion gene, reduced protein levels without harmful side effects in people. That gave them hope that installing the same mutation using base editing might be protective against the disease.

In the new study, the team showed that a base editor installed the R37X edit in human cells efficiently and with few unwanted byproducts. But the researchers needed to deliver the base editors to the brain.

Building on previous work by the vector-engineering lab, the team developed a pair of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) to package and deliver the base-editing machinery to brain cells. They then administered the AAVs to mice infected with the human prion protein.

On average, the system installed the R37X edit in 37 percent of copies of the gene, reducing levels of the prion protein by 50 percent compared to mice without the treatment. The mice also lived about 50 percent longer.

The scientists made a swath of improvements to their system to boost editing efficiency and limit delivery to other tissues. With their improved system, they observed 63 percent lower prion protein levels at a six-fold lower dose of AAVs.

In the future, the team hopes to make the base-editing cargo smaller, because dual AAVs can be costly to produce. They also plan to develop a strategy that uses prime editing — which can install more complicated DNA edits than single-base changes — to install a protective mutation that does not shut down protein production but rather ensures that the prion protein itself is benign.

“There’s still a long way to go to make this a therapy,” the author said. “But it’s really exciting to see how much is possible.”