How cancer escapes cell death and cell division arrest

When cell division (mitosis) takes too long, it can be a sign that something is wrong with the cells, for example DNA damage or chromosomal instability. That’s why our cells come with an innate ability to tell the time, with a stress response known as the mitotic stopwatch pathway activating after prolonged mitosis, and triggering cell cycle arrest, or even cell death. Now, researchers have found that certain cancers can ‘lose their sense of time’ to avoid cellular stress responses, revealing new insights that could shape future anti-cancer therapeutics.

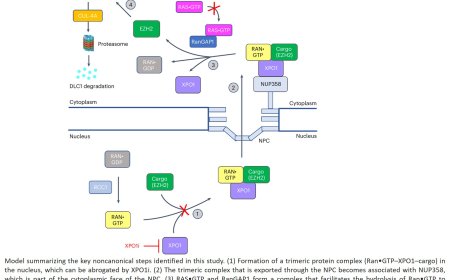

The research published in Nature Communications focuses on a protein called ubiquitin-specific protease 28 (USP28), which is involved in the mitotic stopwatch pathway. USP28 forms part of a complex stabilizing another protein, p53, a known tumor suppressor. The team identified the molecular regions of USP28 that form the essential interactions which bind the complex together, and certain mutations that can help cancers to evade this stopwatch effect.

The corresponding author on the study, explains, “Cells always need to be ready to respond to damage. They constantly produce p53, a protein pivotal to many stress response pathways, responsible for triggering cell cycle arrest or cell death when present in sufficient concentration. It degrades very quickly, so it only reaches sufficient levels when stabilized, for example by being bound into a complex. If this stabilization is blocked, cells can continue dividing, as is the case for cancer. Our goal is to understand the molecular foundations of cancer, to support future treatment efforts.”

Using a combination of experimental methods including live cell imaging and single-cell tracking, alongside theoretical methods such as AlphaFold protein structure prediction, the team revealed the molecular basis of USP28 activity.

The authors demonstrate that USP28 stabilizes p53 through deubiquitination and show that USP28 is required not only for an efficient stress response but also for maintaining basal p53 levels in some cancer cells. Loss of functional USP28 allows cells to evade mitotic stress and DNA damage responses in a manner that is specific to cell type and cancer context.

The researchers identified a prevalent, shorter USP28 isoform critical for p53 stabilization. Its C-terminal domain mediates PLK1-dependent binding to 53BP1, a dimerization-driven interaction necessary for mitotic stress memory, p53 stabilization, and cell cycle arrest.

Cancer-associated missense mutations in this domain disrupt 53BP1 binding, impair nuclear localization, and destabilize USP28, compromising p53 stabilization. The authors found mutations in the 53BP1- binding domain occur more frequently in tumors than those in the catalytic domain, suggesting a potential role in cancer progression

“We found that the C-terminus of USP28 is involved in binding,” says the first author on the study. The C-terminus is one of the ends of a protein chain, characterized by a particular molecular group called a carboxyl. “In many cancers, USP28 has mutations in this region. Our investigations found that these mutations disrupted the protein complex formation, enabling continued cell division and cancer cell proliferation.”

This study is the latest a decade of research from the authors, who have previously reported on several aspects of the mitotic stopwatch pathway mechanisms. However, many mysteries remain.

“We don’t yet know how cells can tell the time. How do they know when 30 or 60 minutes have passed, and when to trigger the mitotic stopwatch?” says the senior author. “And what exactly does the complex look like? We have some structural information, but still lack the complete picture.”

By shining new light on how cancer avoids the mitotic stopwatch pathway, the researchers hope that this information can help inform anti-cancer therapeutics. “Anti-mitotic agents such as paclitaxel are widely used in the treatment of many solid tumors. By uncovering the molecular mechanisms that control mitotic stress responses, we can inform the development of next-generation anti-mitotic therapies and identify which agents are most effective in specific biological or clinical contexts.”