Memory’s hidden architecture uncovered!

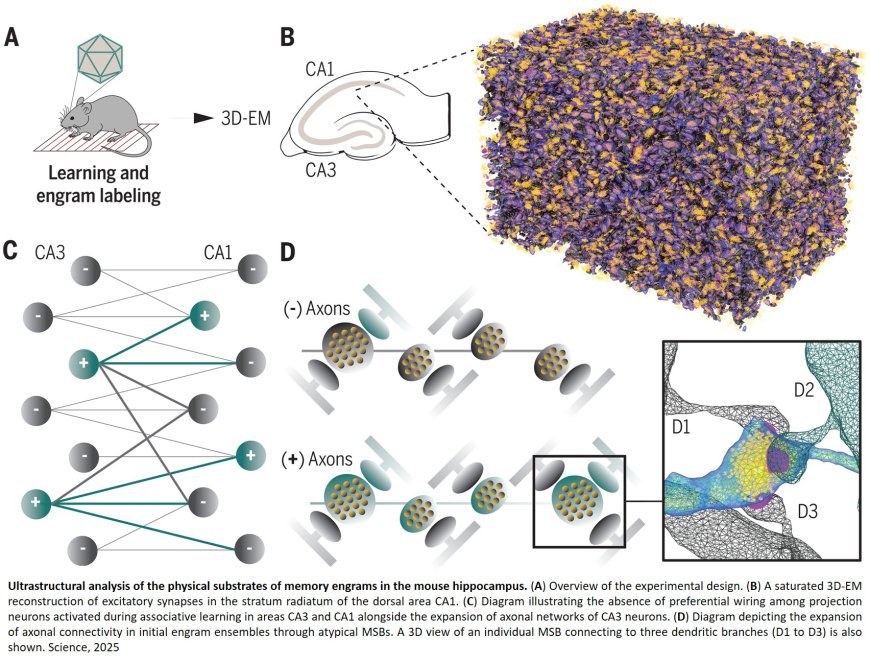

Using cutting-edge genetic tools, 3D electron microscopy, and artificial intelligence, scientists have uncovered key structural hallmarks of long-term memory, called an engram. Their study, published in Science, paves the way for future advances in treating memory loss and other cognitive impairments associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

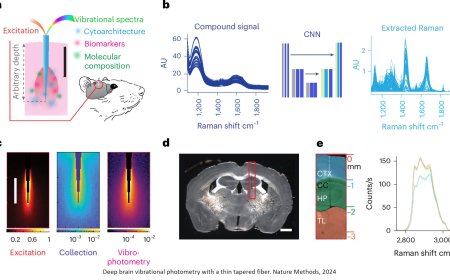

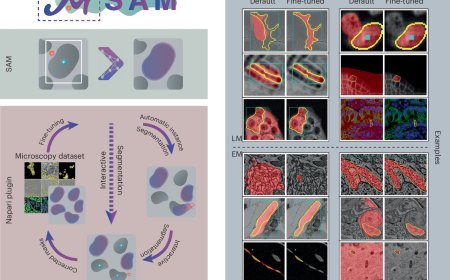

“Our work leverages recent technological developments across multiple fields,” says the study’s lead author. “We used high-resolution 3D imaging to reveal the intricate architecture of brain circuits that store memory traces with unprecedented detail. Since analyzing these images with conventional computer programs could take years, we relied heavily on AI algorithms to accelerate data processing by several orders of magnitude.”

The researchers focused on the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for learning and memory in both animals and humans. They used mouse models to label and identify neurons activated during a specific learning task and, at nanometer-scale resolution, then reconstructed their synaptic connections (the junctions where neurons communicate).

“We hoped to uncover something interesting since no similar approaches had been implemented before,” says the study’s senior author. “What we did not expect was that our findings would challenge two long-standing dogmas.”

At neuronal synapses, chemical signals are typically transmitted from a single nerve terminal—a swollen region of an axon filled with vesicles that secrete these signals—to a single postsynaptic site on the dendrite of a receiving cell. Many previous studies (using lower-resolution optical imaging methods) have suggested that learning requires a bulk increase in synapse number. However, the team found that this is not always the case—the total number and arrangement of isolated synapses remained unchanged after memory formation. Instead, neurons allocated to an engram expanded their connectivity through multi-synaptic boutons (MSBs)—specialized axonal terminals that simultaneously signal to up to six different dendrites rather than just one. These MSBs were not only more abundant along the axons of activated neurons but also structurally more complex.

Secondly, the team discovered that engram neurons in adjacent hippocampal regions do not preferentially connect with each other, counter to what is widely believed in the field. Instead, the expansion of their network through MSBs resulted in the recruitment of other neurons that were not engaged during learning. Moreover, the researchers found that engram neurons exhibited fine-scale alterations in the architecture of their individual synapses, including changes in intracellular organelles such as mitochondria and smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Additionally, these neurons displayed enhanced interactions with astrocytes—glial cells that regulate synaptic function and provide metabolic support.

Researchers now aim to determine whether similar mechanisms operate in other brain circuits and whether their dysfunction contributes to memory loss. Furthermore, MSBs have emerged as promising therapeutic targets.

“We are excited about the possibility of targeting MSBs with drugs to develop new and effective treatments for memory disorders," says the senior author. "However, achieving this goal will require designing new tools to dissect the molecular composition of MSBs, which remains entirely unexplored. We are already making progress in this direction, but much work still lies ahead."

As part of this effort, the researchers are also continuing to refine their AI pipelines to improve the efficiency and accuracy of analyzing large-scale imaging data.