Smells interpreted as taste!

When we eat or drink, we don’t just experience taste, but rather a ‘flavor’. This taste experience arises from a combination of taste and smell, where aromas from food reach the nose via the oral cavity, known as retronasal odor. Researchers have now shown that the brain integrates these signals earlier than previously thought – already in the insula, a brain region known as the taste cortex – before the signals reach the frontal cortex, which controls our emotions and behavior.

“We saw that the taste cortex reacts to taste-associated aromas as if they were real tastes,” explains the lead author. “The finding provides a possible explanation for why we sometimes experience taste from smell alone, for example in flavored waters. This underscores how strongly odors and tastes work together to make food pleasurable, potentially inducing craving and encouraging overeating of certain foods.”

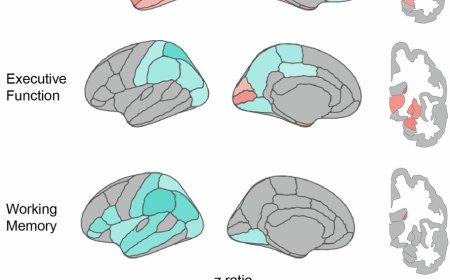

The study involved 25 healthy adults who were first taught to recognize both a sweet taste and a savory taste through combinations of taste and smell. This was followed by two brain imaging sessions using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), in which the participants were given either a tasteless aroma or a taste without smell. The researchers trained an algorithm to recognize patterns in brain activity for sweet and savory tastes, and then tested whether the same patterns could be identified when the participants were only given aromas.

The results showed that aromas that are perceived as sweet or savory not only activated the same parts of the brain’s taste cortex as the actual tastes but that they evoke similar patterns of activation. This overlap was particularly evident in the parts of the taste cortex that are linked to the integration of sensory impressions.

“This shows that the brain does not process taste and smell separately, but rather creates a joint representation of the flavor experience in the taste cortex,” says the study’s last author. “This mechanism may be relevant for how our taste preferences and eating habits are formed and influenced.”

The researchers now plan to investigate whether the same mechanism applies to external smells, known as orthonasal odors.

“We want to find out whether the activation pattern in the brain’s taste cortex changes from salty to sweet when we walk from the cheese aisle to the pastries in the supermarket,” says the author. “If so, this could have a significant impact on the foods we choose to consume.”