Human T-cell receptor–CD3 complex structure unraveled!

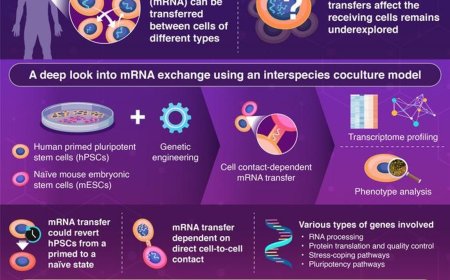

One of the most exciting advances in cancer treatments in the past decade is the development of T cell immunotherapies, in which a patient’s own immune system is trained to recognize and attack dangerous cells. Yet a full understanding of how they actually work has eluded researchers. That’s been a significant limitation, because while T cell immunotherapies are highly effective for certain subtypes of cancers, they’re ineffective for the majority of them—and the reasons why are unclear. Understanding their modus operandi could bring their benefits to a much broader group of cancer patients.

Now researchers have revealed key details about the T cell receptor (TCR), which is embedded in the cell membrane and essential to T cell therapies. Using cryo-EM to image the protein in a biochemical environment that replicates its native milieu, researchers have discovered that the receptor is a sort of jack-in-the-box that springs open when it’s presented with an antigen or similarly suspect particle. This discovery is contrary to all previous cryo-EM studies of the complex.

The novel finding, published in Nature Communications, has the potential to refine and expand T cell therapies.

“This new fundamental understanding of how the signaling system works may help re-engineer that next generation of treatments,” says the first author.

“The T cell receptor is really the basis of virtually all oncological immunotherapies, so it's remarkable that we use the system but really have had no idea how it actually works—and that’s where basic science steps in,” says the senior author.

The lab specializes in visualizing macromolecular complexes, particularly cell membrane proteins, which mediate interactions between the cell interior and exterior. The TCR is one such complex. This intricate, multi-protein structure allows T cells to recognize and respond to antigens presented by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complexes of other cells. It’s this response that T cell therapies have capitalized on to enlist a patient’s own immune system in the cancer fight.

For the study, the researchers aimed to create a native-like environment for the TCR and observe how it behaved. To do so, they put the receptor into a nanodisc, which is a small disc-shaped patch of membrane that is kept in solution by a scaffold protein that wraps around the edge of the disc. It was no mean feat; “getting all eight of these proteins properly assembled into the nanodisc was challenging,” the author says.

All previous structural work on the TCR was performed in detergent, which tends to strip the membrane from the protein. This was the first study in which the complex was put back into a membrane, Walz notes.

They then began cryo-EM imaging. These images revealed that in its resting state, the T cell receptor had a closed, compacted shape. Once activated by an antigen-presenting molecule, it opened up and extended, as if throwing its arms wide.

This came as a deep surprise. “The data that were available when we began this research depicted this complex as being open and extended in its dormant state,” the author explains. “As far as anyone knew, the T cell receptor didn't undergo any conformational changes when binding to these antigens. But we found that it does, springing open like a sort of jack-in-the-box.”

The researchers suggest that combining two key methods made their new view possible. One, they concocted the correct membrane lipid cocktail to replicate the TCR’s in vivo environment. And two, they returned the receptor to that membrane environment using nanodiscs prior to cryo-EM analysis. An intact membrane is key, they discovered, because it holds the TCR in place until activation. By removing the membrane via detergent, previous studies had inadvertently released the latch on the jack-in-the-box, prematurely springing it open.

“It was important that we used a lipid mixture that resembled that of the native T cell membrane,” says the senior author. “If we had just used a model lipid, we wouldn’t have seen this closed dormant state either.”

The researchers are excited about the potential their findings have for optimizing therapies based on T cell receptors. “Re-engineering the next generation of immunotherapies tops the charts in terms of unmet clinical needs,” the author says. “For example, adoptive T cell therapies are being used successfully to treat certain very rare sarcomas, so one could imagine using our insights to re-engineer the sensitivity of those receptors by tuning their activation threshold.”

“This information may be used for vaccine design as well,” the senior author adds. “People in the field can now use our structures to see refined details about the interactions between different antigens presented by HLA and T cell receptors. Those different modes of interaction might have some implication for how the receptor functions—and ways to optimize it.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66939-7

https://sciencemission.com/T-cell-receptor%E2%80%93CD3-complex