Zap-and-freeze’ technique used to watch human brain cell communication

Researchers say they have used a “zap-and-freeze” technology to watch hard-to-see brain cell communications in living brain tissue from mice and humans.

Findings from the new experiments published in Neuron, could potentially help scientists find the root causes of nonheritable forms of Parkinson’s disease, the researchers say.

Sporadic cases of Parkinson’s disease account for most cases of the neurodegenerative disorder, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation. The condition is marked by disruptions to the signaling point between two brain cells. That connection point, known as a synapse, is notoriously difficult to study, says the senior author.

“We hope this new technique of visualizing synaptic membrane dynamics in live brain tissue samples can help us understand similarities and differences in nonheritable and heritable forms of the condition,” the author says. Eventually, he says, this approach could help lead to the development of treatments for the neurodegenerative disorder.

In healthy brains, synaptic vesicles, or message-carrying bubbles within brain cells, help transfer information from cell to cell in a process key to information processing, learning and forming memories. Understanding this process is critical for identifying where cellular communication breaks down in neurodegenerative conditions, the author says.

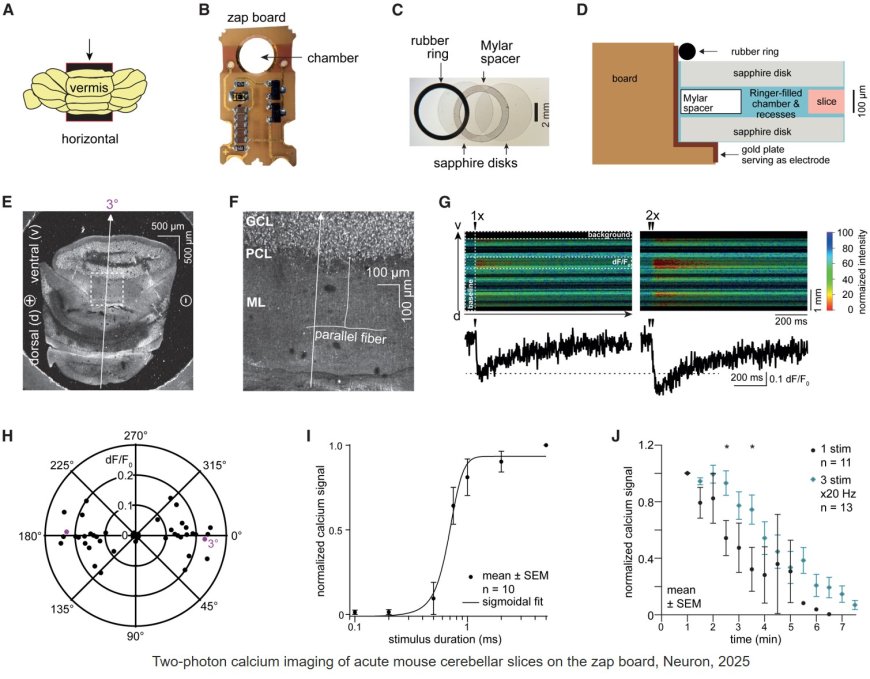

Previously, the senior author helped develop the zap-and-freeze technique to allow for a closer look at synaptic membrane movements (these results were published in 2020 in Nature Neuroscience). Essentially, the technique involves using an electrical pulse to stimulate living brain tissue and then freezing the tissues rapidly to capture cell movement for electron microscopy observation.

In a study published earlier this year in Nature Neuroscience, the author used the approach in the brains of genetically engineered mice to understand how a key protein, intersectin, keeps synaptic vesicles in a particular location within a brain cell until they are ready to be released to activate a neighboring brain cell.

For the new study, the researchers used samples from the brains of normal mice as well as living cortical brain tissue sampled with permission from six individuals undergoing surgical treatment for epilepsy. The surgical procedures were medically necessary to remove lesions from the brain’s hippocampus.

The researchers first validated the zap-and-freeze approach by observing calcium signaling, a process that triggers neurons to release neurotransmitters in living mouse brain tissues.

Next, the scientists stimulated neurons in mouse brain tissue with the zap-and-freeze approach and observed where synaptic vesicles fuse with brain cell membranes and then release chemicals called neurotransmitters that reach other brain cells. The scientists then observed how mouse brain cells recycle synaptic vesicles after they are used for neuronal communication, a process known as endocytosis that allows material to be taken up by neurons.

The researchers then applied the zap-and-freeze technique to brain tissue samples from people with epilepsy, and observed the same synaptic vesicle recycling pathway operating in human neurons.

In both mouse and human brain samples, the protein Dynamin1xA, which is essential for ultrafast synaptic membrane recycling, was present where endocytosis is thought to occur on the membrane of the synapse.

“Our findings indicate that the molecular mechanism of ultrafast endocytosis is conserved between mice and human brain tissues,” the author says, suggesting that the investigations in these models are valuable for understanding human biology.

In future experiments, the senior author says he hopes to leverage the zap-and-freeze technique to study synaptic vesicle dynamics in brain tissue samples taken with permission from patients with Parkinson’s disease undergoing deep brain tissue stimulation.