CLIMBING FIBRES AS TEACHING SIGNALS FOR ASSOCIATIVE CEREBELLAR LEARNING

Nestled at the back of your head, the cerebellum is a brain structure that plays a pivotal role in how we learn, adapting our actions based on past experiences. Yet the precise ways in which this learning happens are still being defined. A study brings new clarity to this debate, with a serendipitous finding of so-called “zombie neurons”. These neurons, alive but functionally altered, have helped to advance our understanding of the cerebellum’s critical teaching signals.

The word “cerebellum” means “little brain”, despite the fact that it holds more than half the brain’s neurons. It is essential for coordinating movements and balance, helping you perform everyday tasks smoothly, like walking down a crowded street, or playing sports. It is also crucial for the learning process that allows you to associate sensory cues with specific actions. Every time you pick up a cup without spilling its contents, effortlessly adjusting the amount of force you apply based on the weight of the container and how full it is, you’re experiencing the consequences of the cerebellum’s ability to link visual signals with corresponding movement responses.

For learning to take place, the cerebellum continuously monitors the outside world and the outcome of movements that we make within it. When we make a mistake, information about our errors can be used to adjust the strength of brain connections, leading over time to changes in our behavioural responses to specific cues.

However, it is not known exactly how such “error” or “teaching signals” are represented within the brain to drive learned changes in behaviour. The latest research published in Nature Neuroscience, provides compelling evidence that activity in a specific class of cerebellar inputs, called climbing fibres, are absolutely essential for associative learning to occur.

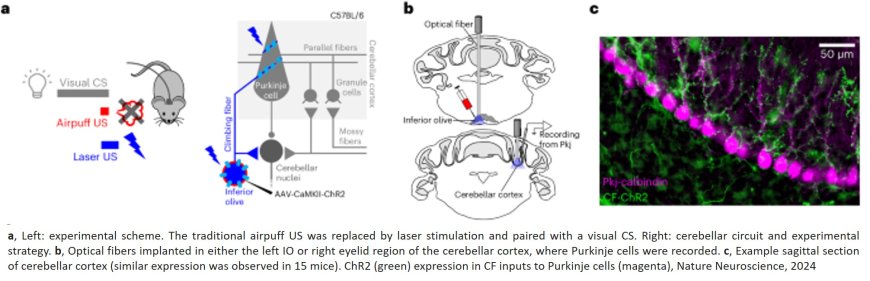

To examine the role of climbing fibres and their targets, cerebellar Purkinje cells, in learning, the researchers designed an experiment involving mice. They used a common learning task known as eyeblink conditioning. In this task, a mouse learns to blink in response to a certain signal, such as a light, which precedes an event, typically a gentle puff of air aimed at its eye. The animals then display associative learning, learning to link a sensory signal with an adaptive movement response, in this case, blinking.

“In our experiment”, explains the study’s first author, “we used a technique called optogenetics. This method functions like a highly precise remote control for brain cells, using light to turn on or off certain cells of interest at extremely specific times”. The author continues, “Climbing fibres normally respond to sensory stimuli like a puff of air to the eye. By precisely activating these fibres with optogenetics, we were able to trick the mouse into thinking it had received an air puff, when in fact it had not. After we consistently stimulated climbing fibres during the presentation of a visual cue, the mice learned to blink in response to that cue - even in the absence of stimulation. This proved that these fibres are sufficient to drive this type of associative learning”.

The authors were further able to show that climbing fibres are also necessary for associative learning. “When we used optogenetics to selectively silence climbing fibres during the presentation of an actual air puff”, the author reveals, “the mice completely failed to learn to blink in response to the visual cue”. The team similarly manipulated a number of other types of brain cells within the cerebellum, but found that none of them were able to provide such reliable teaching signals for learning.

Looking more closely at some of their data, the researchers discovered an unexpected twist. In order to manipulate climbing fibre activity using optogenetics, they had used genetic tools to express a light-sensitive protein called Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in those neurons. Surprisingly, they found that when they tried to teach the ChR2-expressing mice using the traditional air puff method, the animals completely failed to learn. As Carey explains, after systematic recordings of neural activity from the cerebella of these mice, “It turned out that introducing ChR2 into the climbing fibres altered their natural properties, preventing them from responding appropriately to standard sensory stimuli like air puffs. This, in turn, completely blocked the animals’ ability to learn”.

“The remarkable thing,” says the author, “was that these same mice learned perfectly well when we paired climbing fibre stimulation, instead of an air puff, to a visual cue.” Unintentionally, the team had achieved a long-standing objective in neuroscience: to modulate specific patterns of activity within specific neurons without entirely shutting down their communication, resulting in a more natural intervention to elucidate their causal role. In other words, although the climbing fibres remained spontaneously active and were cl