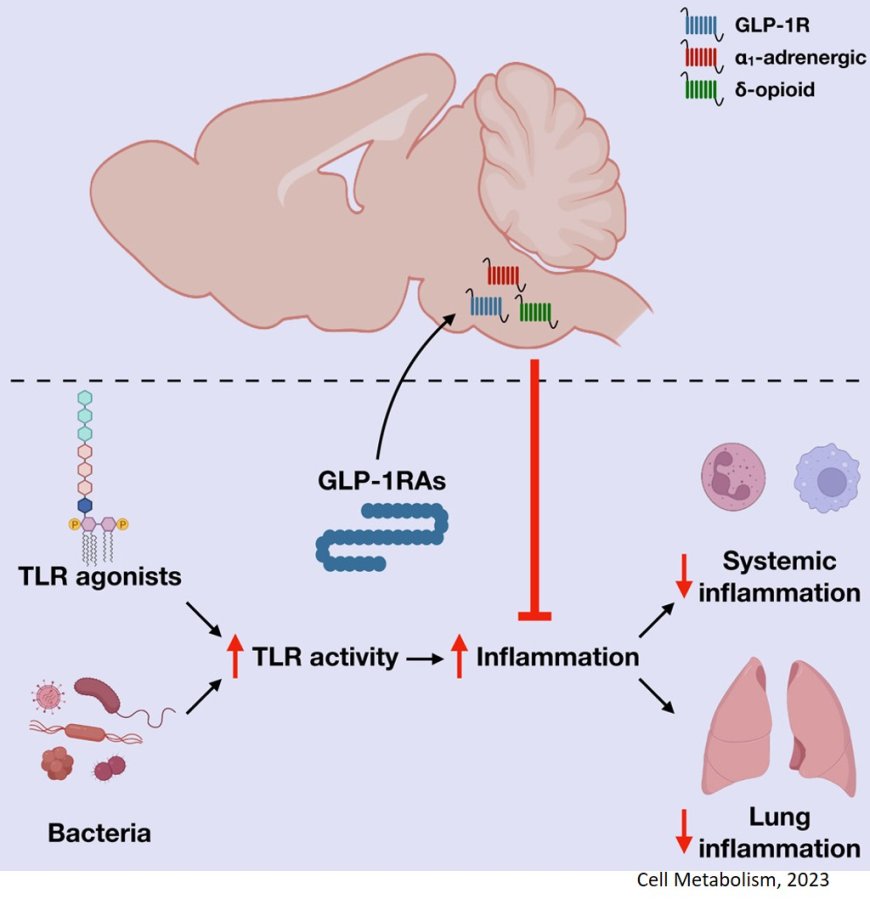

GLP-1-brain-immune axis to control inflammation

The GLP-1-based diabetes drugs are named 2023 breakthrough of the year by the Science Magazine.

Not only have millions of people with type 2 diabetes benefitted from GLP-1 agonists, but the drugs also produced wide-ranging health benefits beyond weight loss in two recent patient trials.

For years, GLP-1 agonists have been known to have a fortuitous side effect of improving metabolic health, but how this is regulated in the body remains unclear.

The team have discovered a gut-brain-immune network that controls inflammation across the body affecting organ health.

The research, published in the journal Cell Metabolism holds promise for understanding and treating metabolic diseases.

Known as GLP-1 receptor agonists, for glucagon like peptide 1, these medications mimic the gut hormone GLP1, which regulates blood sugar levels and appetite. Among them are the popular weight loss jabs but similar compounds have been used for more than 18 years to treat type 2 diabetes.

"One of the really interesting things about the GLP-1 drugs is that beyond the control of blood sugar and body weight they also seem to reduce the complications of chronic metabolic disease.” said the senior author.

Research has found that some drugs in these group may lower the risk of heart disease, such as heart failure, stroke, fatty liver disease and kidney disease.

“We know from clinical studies that GLP-1 does all this amazing stuff in people, but we don't fully know how they work”, said the author.

It’s why these drugs are in the limelight.

“For all their promise, GLP-1 agonists have raised more questions than they have answered – a hallmark of a true breakthrough,” wrote Science journals’ editor-in-chief, in an Editorial in the latest issue of Science.

Now, the team has focused on teasing out how GLP-1 drugs reduce inflammation, which is a common factor in chronic metabolic diseases. Inflammation is the process by which the immune system recognizes and removes foreign agents such as viruses and bacteria and promotes healing. In chronic form, however, it can persist without an external cause and lead to organ damage.

Given that immune cells are embedded within most organs, an obvious assumption was that the drugs dampen inflammation by interacting with GLP-1 receptors on the immune cells. This is the case in the gut, where large numbers of immune cells are activated by GLP-1. But in other organs, the number of immune cells containing GLP-1 receptors is negligible, indicating another mechanism to be at play.

“The strange thing is that you can’t find many GLP-1 receptors in all these other organs where GLP-1 seems to work,” said the author.

The author had a hint that the brain might be involved for two reasons: the GLP-1 receptors are abundant in the brain, and the brain and the immune system communicate with all organs in the body.

For the study, the authors induced systemic inflammation in mice by either injecting them with a bacterial cell wall component or a bacterial slur to induce sepsis, an extensive inflammation throughout the body that leads to organ damage. Remarkably, GLP-1 agonists reduced inflammation, but only when its receptors in the brain were left unblocked. When these brain receptors were pharmacologically inhibited or genetically removed in mice, the drugs’ ability to reduce inflammation was lost.

The findings demonstrated for the first time that there is a GLP-1-brain-immune axis that controls inflammation across the body independent of weight loss, even in peripheral organs devoid of GLP1 receptors, said the author.

The work is far from complete, however. The team is now trying to pinpoint the brain cells that interact with GLP-1. They are also looking at various mouse models of inflammation, including heart disease, atherosclerosis, and liver and kidney inflammation, to establish whether the beneficial effects of GLP-1 in each case are indeed mediated through the brain.