How the gut builds long-lasting immunity after viral infections

A new has shown that immune cells in the gut follow an atypical pathway to produce antibodies that provide long-term protection against viruses.

The findings, which were published in the journal Cell, could help guide the development of better vaccines for respiratory viruses like influenza, SARS-CoV-2 and bird flu.

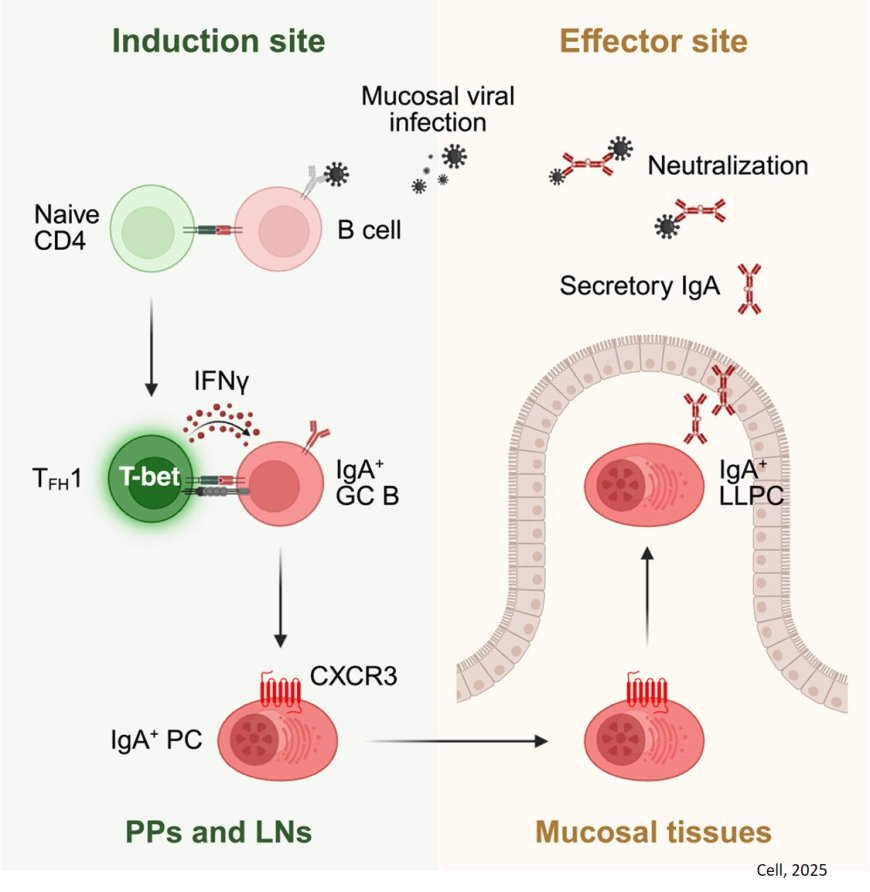

While COVID-19 and flu vaccines reduce the risk of severe complications of illness, they are less effective at preventing infections at the outset. To protect against infection, a vaccine must activate a strong immune response at the places where a virus typically gains entry — the nose, mouth and airways. This so-called mucosal immunity relies on an antibody called IgA, which is concentrated in the mucous membranes lining your respiratory and digestive tracts and secreted through bodily fluids like saliva and tears.

“If you could make a mucosal immune response that’s durable, that’s the Holy Grail because then you’re blocking entry of the virus,” says the study’s senior author.

“If you block entry, then you’re not going to get infected and you’re not going to transmit the virus.”

One of the biggest challenges in developing a mucosal vaccine has been figuring out how to create a long-lasting IgA response.

Previously the authors have shown that even though natural infections with viruses like SARS-CoV-2 do generate a local immune response, those responses fade quickly.

“When we looked at the key IgA antibody that protects us against infection, those antibody levels really don’t last,” the author says.

At the same time, researchers also knew that a long-lasting, vaccine-induced IgA response was possible.

“We know that oral vaccination against rotavirus and polio gives you lifelong immunity, so we hypothesized that maybe there was something about the oral route and the small intestine that could allow for a long-lived IgA response,” says the senior author.

To test their hypothesis, the research team turned to a mouse model of rotavirus infection with the goal of better understanding how virus-specific IgA immune responses are generated.

They found that while the gut IgA response depends on crosstalk between two types of immune cells, T cells and B cells, it skips a key step where parts of the virus are first presented to T cells, thereby allowing for a faster IgA antibody response. Moreover, the IgA produced in response to the virus were protective and lasted for at least 200 days after the initial infection.

“The IgA response was shockingly long lived,” says the senior author.

“Despite the virus being cleared within about 10 days, the response continued to improve over time, so you end up having IgA antibodies that are very, very good at recognizing rotavirus.”

The author thinks there may be something unique about the gut environment — for example, its anatomy and rich microbial community — that enables it to generate such a durable and effective immune response. These findings support the potential of oral vaccination as a strategy to protect against respiratory viruses, but the author notes that there are also significant hurdles to creating an oral vaccine.