How female gametes control fertilization recovery in flowering plants

Researchers have revealed that the female gamete in flowering plants controls fertilization recovery by secreting pollen tube attractants.

The researchers, who explored why ovules continue to attract pollen tubes after failed double fertilization, have also provided molecular clues for the survival of some plant species after the loss of synergid cells during evolution.

The study was published in Cell.

Seed production by fertilization is essential for plant reproduction and seed crop yield. As early as 1904, botanists observed the interesting phenomenon of more than one pollen tube being attracted into an ovule. This process, called "fertilization recovery," was thought to be caused by fertilization failure. This failure was presumed to trigger the attraction of extra pollen tubes, thus rescuing fertilization by bringing in more sperm cells. The underlying mechanism was not explained, however.

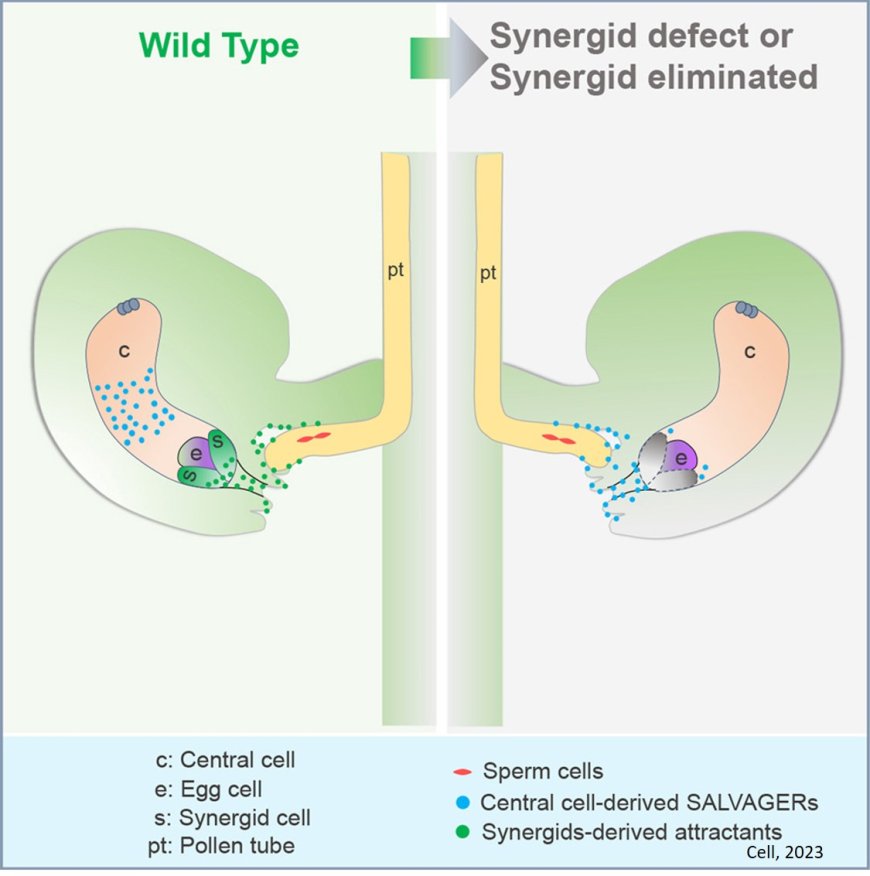

Generally, the embryo sac of flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) contains two synergid cells, two female gametes (i.e., one egg cell and one central cell), and three antipodal cells. Over the past two decades, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated that synergid cells play a critical role in secreting pollen tube attractants, thereby facilitating successful fertilization. Scientists had proposed that these two synergid cells give the plant a second chance to restore fertilization if the first synergid fails to attract a pollen tube containing two fertile sperm cells.

However, recent research has shown that Arabidopsis thaliana ovules, with their two synergid cells experimentally removed, can still attract pollen tubes and produce seeds. This observation suggested the existence of an alternative mechanism for fertilization recovery.

A previous study by the group suggested that the central cell, as an endosperm precursor, is also critical for pollen tube attraction. To investigate whether the central cell could secrete a pollen tube attractant, the researchers measured the pollen tube attraction activity of more than a hundred secreted peptides expressed in the central cell. They eventually found that two of them, SALVAGER1 (SAL1) and SAL2, show pollen tube attraction activity and can bind to the pollen tube plasma membrane.

Interestingly, they found that SAL1/2 localized in the central cell are secreted into the micropyle and funiculus when synergid cells are defective or eliminated by the gcs1 mutant pollen tubes, which carry infertile sperm cells. These results suggest that SALs are new types of pollen tube attractants.

In addition, sal1/2 knockout mutants lost the ability, controlled by female gametes, to restore fertilization. Subsequent investigations revealed functional redundancy between SAL1/2 and the synergid cell attraction system in successful fertilization.

Furthermore, a similar study conducted on Arabidopsis lyrata, a sister species of Arabidopsis thaliana, demonstrated the evolutionary conservation of the central-cell-secreted SALs in the fertilization recovery mechanism.

In summary, the researchers have uncovered a central-cell-controlled fertilization recovery mechanism that is important for ensuring reproduction success.