A new type of immune defense in E. coli

Scientists have discovered a new type of immune defense in E. coli bacteria that turns viral infection machinery against the virus itself. Named after the Chinese military strategist Kongming—who famously used enemy weapons to defeat them—the system reveals a novel immune signaling pathway. This discovery could inform the development of future biotech tools and phage therapy as an alternative to antibiotics.

Over 1800 years ago in China, legendary military strategist Zhuge Liang, known as Kongming, faced a superior force. But instead of making his own weapons, he had the enemy deliver them to him. Using empty boats covered in straw, he tricked the enemy into firing thousands of arrows at the boats. After the battle, his army collected the arrows and used them themselves.

Now, new research shows that bacteria have developed a similar defense strategy in their fight against viral attacks.

The newly discovered immune system, which the researchers have dubbed Kongming, allows an attacking virus to bring about its own defeat. When a virus infects the bacteria, Kongming uses one of the virus' own enzymes to activate a deadly defense that stops the infection.

The researchers discovered the Kongming defense system in E. coli, a bacterium which is commonly found in our intestines. However, they identified variants of the Kongming system across diverse bacteria in the environment, indicating that this antiviral strategy is widespread.

The research is published in the scientific journal Science .

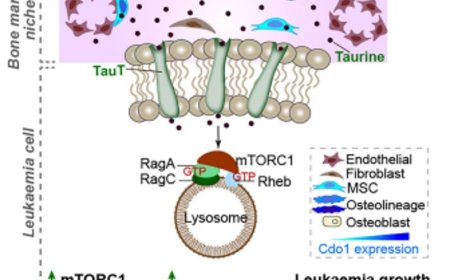

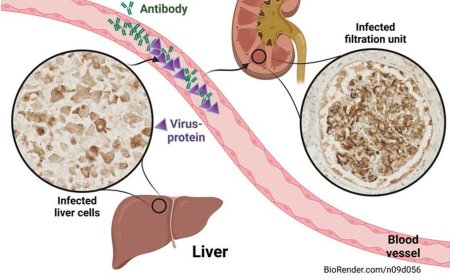

When a virus attacks bacteria, it needs to copy its own genetic material in order to spread quickly. To do this, some viruses use specialized enzymes called a nucleotide kinases, which helps to rapidly produce the building blocks required for the genetic information to be replicated.

Kongming defense hijacks the enzyme to make something completely different – an immune signal molecule that instead triggers a defense against the virus. This signal causes the bacterium to commit suicide, which stops the virus.

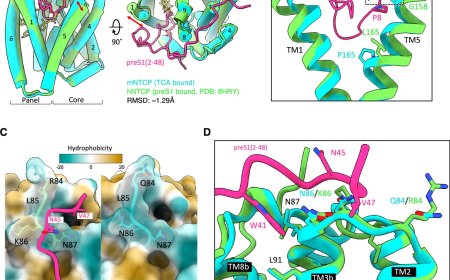

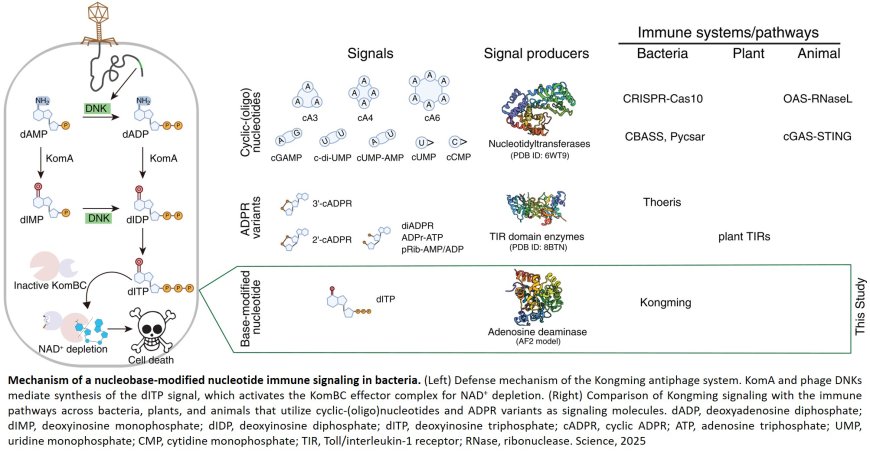

The authors show that KomA and phage DNKs mediate synthesis of the dITP signal, which activates the KomBC effector complex for NAD+ depletion.

“The bacterium sacrifices itself to stop the virus—which may sound dramatic, but it’s an incredibly effective strategy. By dying, it takes the virus down with it, preventing the infection from spreading to other bacteria in the population. It’s a bit like blowing up a bridge to stop an advancing enemy”, explains the author.

But are viruses defenseless against this strategy? Not at all—some have evolved countermeasures in the ongoing arms race with Kongming.

Bacterial infections have challenged humanity since the dawn of time, and antibiotics have long been our main line of defense. But in recent decades, the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, mainly due to antibiotic overuse, has become a major global health concern.

One promising alternative is phage therapy: the use of viruses that specifically infect and kill unwanted bacteria. But bacteria aren’t defenseless; they’ve evolved a wide arsenal of antiviral strategies, including systems like Kongming, that can block phage infection.

“To develop effective phage therapies, we need to understand the natural immune systems bacteria use to resist viral attacks,” says the author. “By characterizing defenses like Kongming—and the tricks phages used to bypass them—we can better design phage therapy strategies and improve their clinical success.”

Furthermore, the molecular machinery driving Kongming may also be harnessed for future biotechnological applications. The signaling molecule that specifically activates the system—dITP—has also been linked to human diseases, including cancer. Because Kongming’s immune effector complex is highly specific to this molecule, it may inspire new tools in synthetic biology and diagnostics.

“Since the Kongming immune effector complex specifically responds to dITP, it could be used to detect this non-canonical nucleotide—opening the door to interesting biotechnological applications,” concludes the author.

In the research, the Kongming defense was discovered in Escherichia coli (E. coli), a common bacteria found in both our guts and the environment. But because defense systems spread between bacteria, Kongming is found in many other bacterial species that live in soil, oceans or even in our bodies.

When it comes to viruses, Kongming protects bacteria against so-called bacteriophages - a special type of virus that only attacks bacteria. The specific bacteriophages that the researchers investigated include:

This strategy inspired the naming of the newly discovered bacterial immune system Kongming, as bacteria use a similar tactic: they hijack the virus' own enzymes and turn them against the attacker.

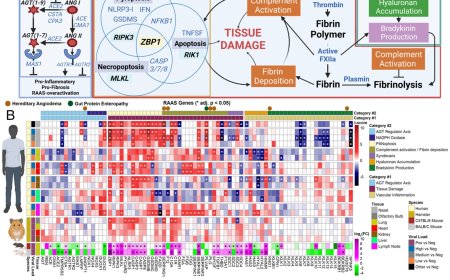

When the Kongming system is activated, the bacteria produce a signaling molecule called dITP, which triggers the activation of specialized proteins that quickly drain the cell of NAD+ - a vital molecule. Although the individual bacterium sacrifices itself, the mechanism ensures that the virus cannot spread and the rest of the bacterial population survives.