Maternal protein diet modulates the facial appearance of the offspring

The protein content of the diet during pregnancy can affect the face of the offspring. This is shown in animal studies, and the underlying mechanism was also found in human genetic studies.

A child is expected to share facial features with their parents. However, the face is also influenced by factors beyond genetics, so-called environmental factors. Among those, lifestyle during pregnancy is an essential factor. For example, extensive alcohol consumption during pregnancy can lead to facial abnormalities in the child.

The current study, published in Nature Communications, revealed a novel link between the child’s face and pregnancy lifestyle, specifically protein intake during pregnancy.

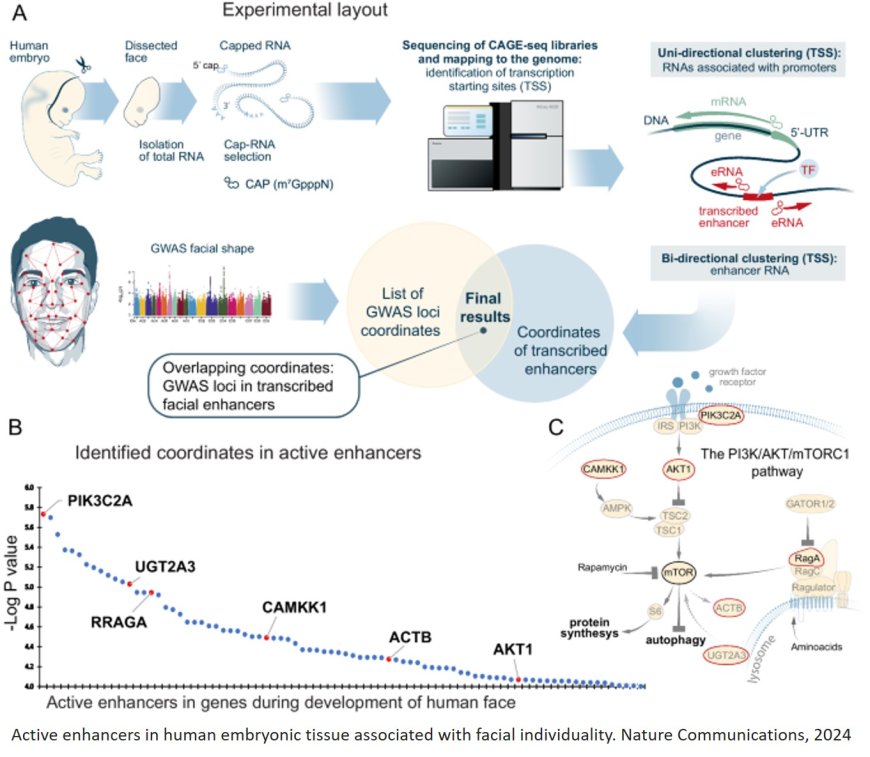

A research team delved into the mechanisms that control the formation of the facial bone structure during the embryonic phase. The studies revealed that a particular signaling pathway in the cells seemed to play a crucial role in shaping the face.

The signaling pathway, known as mTOR, controls several cell functions, including cell division and cell survival, and is known to be the target of an immunosuppressive medicinal product, rapamycin, which is administered during organ transplantation to avoid rejection.

The mTOR signaling pathway acts as an intracellular nutritional sensor specifically tailored to amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. The researchers found that the mTOR pathway modulates the formation of facial skeletal structures in humans, mice, and zebrafish. This led researchers to investigate whether the protein content of the pregnancy diet affects mTOR and plays a role in the formation of the facial bone structure.

Pregnant mice were given diets with high and low protein levels. As expected, the protein levels in the female's diet were consistent with the activity level of mTOR in the developing face. In newborn offspring, the differences in the face were noticeable, albeit subtle.

“It is difficult to describe the exact effects, which can be caused by protein content in the diet during human pregnancy. But our data suggest that the mechanism is evolutionarily conserved and, from this perspective, likely serves to increase variability in the feeding apparatus, thus, allowing animals to adapt to various feeding sources in the wild. In mice, we see, for example, an enlarged nasal cavity in the offspring of mice fed a protein-enriched diet and a slightly elongated jaw in mice where the mother has eaten a low-protein diet,” says the author.

The aim has been to contribute to the future development of more effective clinical methods for the prevention and treatment of different types of facial congenital malformations and to increase knowledge of what a good pregnancy diet should contain.

“The findings emphasize the importance of maintaining a well-balanced diet during pregnancy, with particular attention to protein intake. The insights open new avenues for understanding the intricate interplay between genetics, lifestyle, and the formation of our unique facial features,” concludes the author.