The role of microglia in neurodegenerative diseases

Inflammation is triggered by the immune system and is part of the body’s natural response to injuries or disease. However, abnormal inflammation has recently been established as a hallmark for pathologies that were previously not inherently considered as immune-related. This is the case for several neurologic diseases, in which the evidence of a dysregulated neuroinflammatory state is ever-growing.

The main immune cells in the Central Nervous System (CNS) are called microglia and can be considered the brain’s resident macrophages. They are, therefore, in charge of triggering inflammation in the brain, when necessary. In addition, microglia are part of a wide network of essential mechanisms keeping a proper brain function, including remodelling of synaptic connectivity and myelination. However, when exposed to nefarious stimuli, microglia transition from a resting elongated and ramified form to an activated amoeboid state, coupled with an overall enhanced pro-inflammatory phenotype.

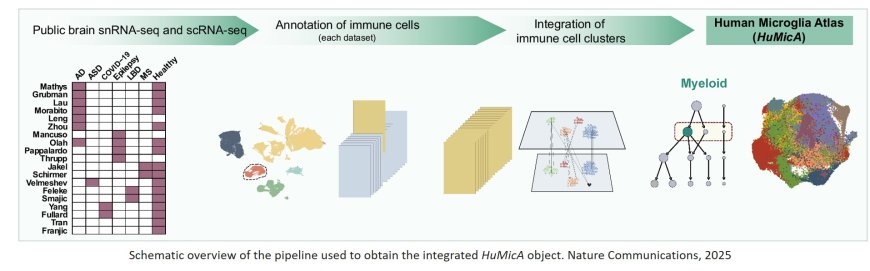

Early evidence using bulk analysis proposed a mechanism in which pro-inflammation would be considered neurotoxic but, with the emergence of single-cell technologies, the understanding of transcriptomic modifications in neurodegenerative diseases grew significantly. This better understanding led to the description of the disease-associated microglia (DAM) phenotype, that has served as the gold standard of microglia dysregulation in pathology. Notwithstanding, the scalability of microglia single-cell analysis remained a challenge since they only account for 5% of human brain cells, making it difficult to characterize smaller subpopulations with more specific phenotypes.

A research team has developed a tool to overcome this limitation: the Human Microglia Atlas (HuMicA), composed of 90,716 myeloid cells and supplied as a public resource. According to the lead author, “the HuMicA serves to help the elucidation of microglia’s role in disease, but also to better understand the biology of microglia itself. The DAM signature is insufficient to fully comprehend microglia’s behaviour in disease, and high-scale studies allow to break it down into more specific and insightful subpopulations. We consider that the HuMicA’s contributions to the field do not end here, as it is intended to be used as an open source by the community.”

The study has been recently published in the top journal Nature Communications and is the result of an integrated analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data of human microglia across six pathologies: Alzheimer’s Disease, autism spectrum disorder, epilepsy, COVID-19, Lewy Body Diseases (including Parkinson’s disease) and Multiple Sclerosis, in comparison to healthy controls.

The findings reveal nine subpopulations, demonstrating that microglia exist under the form of transcriptionally distinct groups of cells. One of these showed a signature associated with the DAM phenotype coupled with lipid metabolism (GPNMB-high Lipo.DAM) and were expanded in Alzheimer Disease and Multiple Sclerosis. Experimental evidence corroborates part of the results and raises the question on the relevance of this population in other diseases.