Newly discovered purging process in gastric cells

When injured, cells have well-regulated responses to promote healing. These include a long-studied self-destruction process that cleans up dead and damaged cells as well as a more recently identified phenomenon that helps older cells revert to what appears to be a younger state to help grow back healthy tissue.

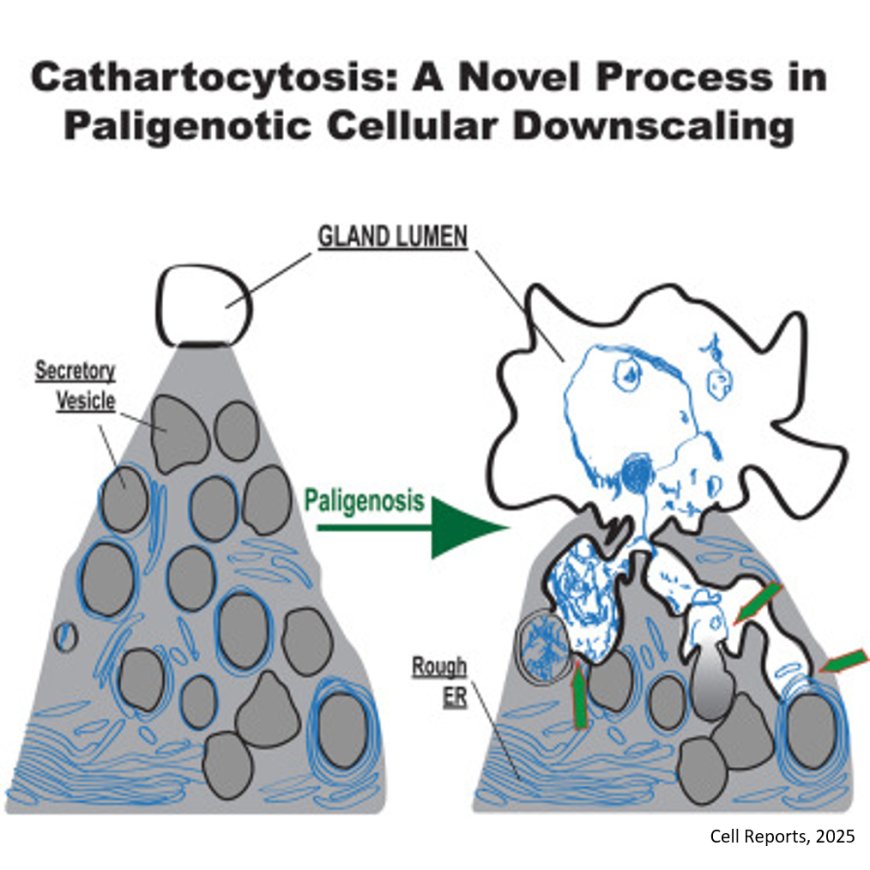

Now, a new study in mice reveals a previously unknown cellular purging process that may help injured cells revert to a stem cell-like state more rapidly. The investigators dubbed this newly discovered response cathartocytosis, taking from Greek root words that mean cellular cleansing.

Published in the journal Cell Reports, the study used a mouse model of stomach injury to provide new insights into how cells heal, or fail to heal, in response to damage, such as from an infection or inflammatory disease.

“After an injury, the cell’s job is to repair that injury. But the cell’s mature cellular machinery for doing its normal job gets in the way,” said the first author. “So, this cellular cleanse is a quick way of getting rid of that machinery so it can rapidly become a small, primitive cell capable of proliferating and repairing the injury. We identified this process in the GI tract, but we suspect it is relevant in other tissues as well.”

The author likened the process to a “vomiting” or jettisoning of waste that essentially adds a shortcut, helping the cell declutter and focus on regrowing healthy tissues faster than it would be able to if it could only perform a gradual, controlled degradation of waste.

As with many shortcuts, this one has potential downsides: According to the investigators, cathartocytosis is fast but messy, which may help shed light on how injury responses can go wrong, especially in the setting of chronic injury. For example, ongoing cathartocytosis in response to an infection is a sign of chronic inflammation and recurring cell damage that is a breeding ground for cancer. In fact, the festering mess of ejected cellular waste that results from all that cathartocytosis may also be a way to identify or track cancer, according to the researchers.

The researchers identified cathartocytosis within an important regenerative injury response called paligenosis, which was first described in 2018.

In paligenosis, injured cells shift away from their normal roles and undergo a reprogramming process to an immature state, behaving like rapidly dividing stem cells, as happens during development. Originally, the researchers assumed the decluttering of cellular machinery in preparation for this reprogramming happens entirely inside cellular compartments called lysosomes, where waste is digested in a slow and contained process.

From the start, though, the researchers noticed debris outside the cells. They initially dismissed this as unimportant, but the more external waste they saw in their early studies, the more the authors began to suspect that something deliberate was going on. They utilized a model of mouse stomach injury that triggered the reprogramming of mature cells to a stem cell state all at once, making it obvious that the “vomiting” response — now happening in all the stomach cells simultaneously — was a feature of paligenosis, not a bug. In other words, the vomiting process was not just an accidental spill here and there but a newly identified, standard way cells behaved in response to injury.

Although they discovered cathartocytosis happening during paligenosis, the researchers said cells could potentially use cathartocytosis to jettison waste in other, more worrisome situations, like giving mature cells that ability to start to act like cancer cells.

While the newly discovered cathartocytosis process may help injured cells proceed through paligenosis and regenerate healthy tissue more rapidly, the tradeoff comes in the form of additional waste products that could fuel inflammatory states, making chronic injuries harder to resolve and correlating with increased risk of cancer development.

“In these gastric cells, paligenosis — reversion to a stem cell state for healing — is a risky process, especially now that we’ve identified the potentially inflammatory downsizing of cathartocytosis within it,” the author said. “These cells in the stomach are long-lived, and aging cells acquire mutations. If many older mutated cells revert to stem cell states in an effort to repair an injury — and injuries also often fuel inflammation, such as during an infection — there’s an increased risk of acquiring, perpetuating and expanding harmful mutations that lead to cancer as those stem cells multiply.”

More research is needed, but the authors suspect that cathartocytosis could play a role in perpetuating injury and inflammation in Helicobacter pylori infections in the gut. H. pylori is a type of bacteria known to infect and damage the stomach, causing ulcers and increasing the risk of stomach cancer.

The findings also could point to new treatment strategies for stomach cancer and perhaps other GI cancers. The authors have developed an antibody that binds to parts of the cellular waste ejected during cathartocytosis, providing a way to detect when this process may be happening, especially in large quantities. In this way, cathartocytosis might be used as a marker of precancerous states that could allow for early detection and treatment.

“If we have a better understanding of this process, we could develop ways to help encourage the healing response and perhaps, in the context of chronic injury, block the damaged cells undergoing chronic cathartocytosis from contributing to cancer formation,” the author said.

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(25)00841-1