How scratching promotes allergic inflammation

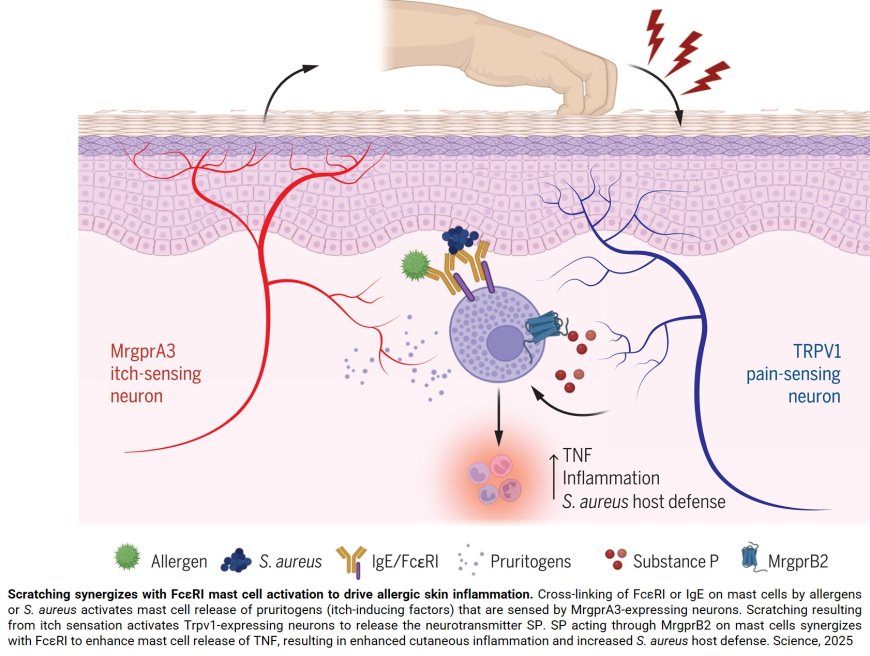

New research uncovers the dual nature of scratching an itch; although it can worsen skin inflammation, it can also boost immune defenses against bacterial infections at the injury site.

The findings shed light on a pharmacologically targetable pathway that explains how scratching triggers inflammation, resolving the paradox of scratching as both a harmful pathological process and a beneficial evolutionary adaptation.

Scratching is a natural, instinctive response to the sensation of itching, and it plays a central role in many skin conditions and injuries, such as dermatitis and insect bites, where chronic itching can be a major source of discomfort.

Scratching can aggravate the condition by promoting inflammation in a self-perpetuating "itch-scratch cycle," where the scratching intensifies the itch and can exacerbate the injury.

Yet unlike pain, which typically causes an aversion response, scratching can feel pleasurable, which suggests it might serve some adaptive benefit. However, the mechanisms by which scratching contributes to skin inflammation and whether the itch-scratch reflex offers any benefits to the host remain poorly understood.

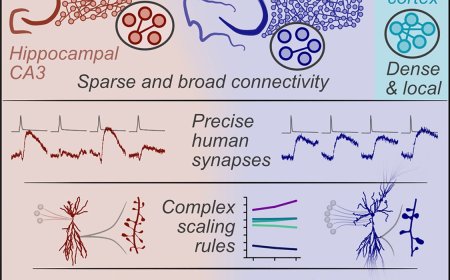

Using a novel genetically modified mouse model, the researchers explored how eliminating the function of itch-sensing neurons called nonpeptidergic 2 (NP2) characterized by the expression of MrgprA3 (called Mrgpra3DTR), affects the connection between itch, scratch and inflammation.

The researchers discovered that scratching activates pain-sensing neurons (TRPV1) that release substance P (SP), which stimulates mast cells to increase inflammation, mainly by attracting neutrophils.

This was confirmed using mice with a genetic ablation of MrgprB2 or the gene encoding SP (Tac1) and by chemogenetic inhibition of Trpv1-expressing neurons. Inflammation in mice prevented from scratching could be rescued by exogenous activation of Trpv1-expressing neurons.

However, while scratching can aggravate issues like dermatitis, it may also help host immune defense by reducing bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, during infections.

Moreover, scratching can influence the skin's microbiome at the injury site, potentially preventing microbiota imbalances, although chronic conditions like atopic dermatitis complicate this.

According to the authors, the findings suggest that scratching serves both as a pathological driver of inflammation and an evolutionary mechanism to bolster protection against infection.