Basal stem-like cells identified as origin of small cell lung cancer

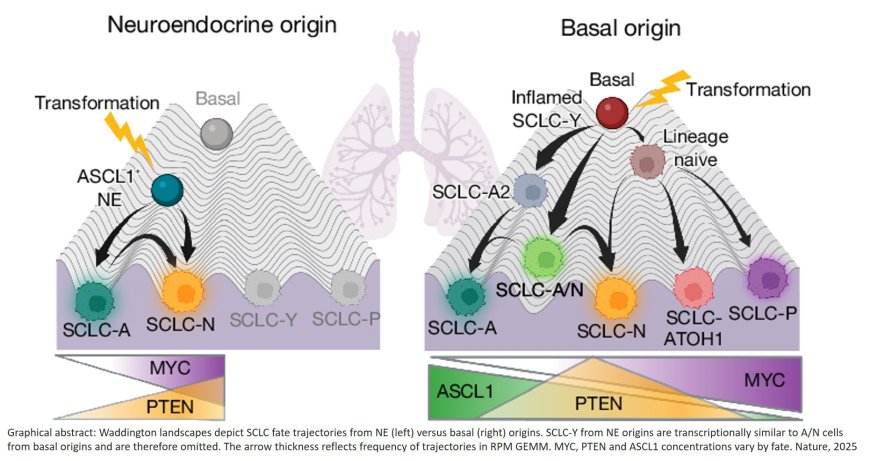

A new study reveals that small cell lung cancer (SCLC) likely begins in basal stem-like cells rather than in neuroendocrine cells, marking a major shift in the understanding of this aggressive disease that is often associated with smoking.

For decades, scientists have thought SCLC begins in specialized lung cells known as neuroendocrine cells. The study published in the journal Nature – shows basal cells (which have the ability to regenerate multiple lung cell types) can give rise to tumors in both the classic neuroendocrine form and a tuft-like form.

The tuft-like form is associated with poor patient outcomes and resistance to current therapies. By pinpointing that basal cells can form both tumor states, researchers can now explore strategies to prevent the disease before it evades the immune system and spreads.

“This discovery reshapes our understanding of how small cell lung cancer begins,” said the study’s senior author.

“Our models, for the first time, reflect the full complexity of the disease,” the author said, “allowing us to study and target its most dangerous forms.”

Using genetically engineered mice, 3D tumor organoids, and the largest-available dataset of human SCLC tumors (at 944 samples), researchers also discovered the tuft-like tumors were only triggered when genetic changes (high MYC, PTEN loss and ASCL1 suppression) were introduced into basal cells – not neuroendocrine cells – suggesting a fundamental shift in how scientists understand the disease.

“We used a technique called lineage barcoding that allowed us to tag individual cells and track how they evolve over time,” said the study’s first author.

“This revealed that small cell lung cancer cells can shapeshift through a process called cell fate plasticity,” the author said, “which helps explain why the disease resists treatment and could provide new approaches for how we might block their transition into aggressive cancer.”

Researchers said this discovery creates the first accurate lab models of the most treatment-resistant tuft-like form of SCLC. The models, in combination with new foundational understanding, allow for advancement in the study of early detection and targeted therapies.

“We now have the tools to explore how the immune system interacts with these basal cells before they transform into aggressive cancer. That opens the door to therapies that could stop the disease before it even starts,” said the senior author.