Jaundice-associated pigment in protecting against malaria

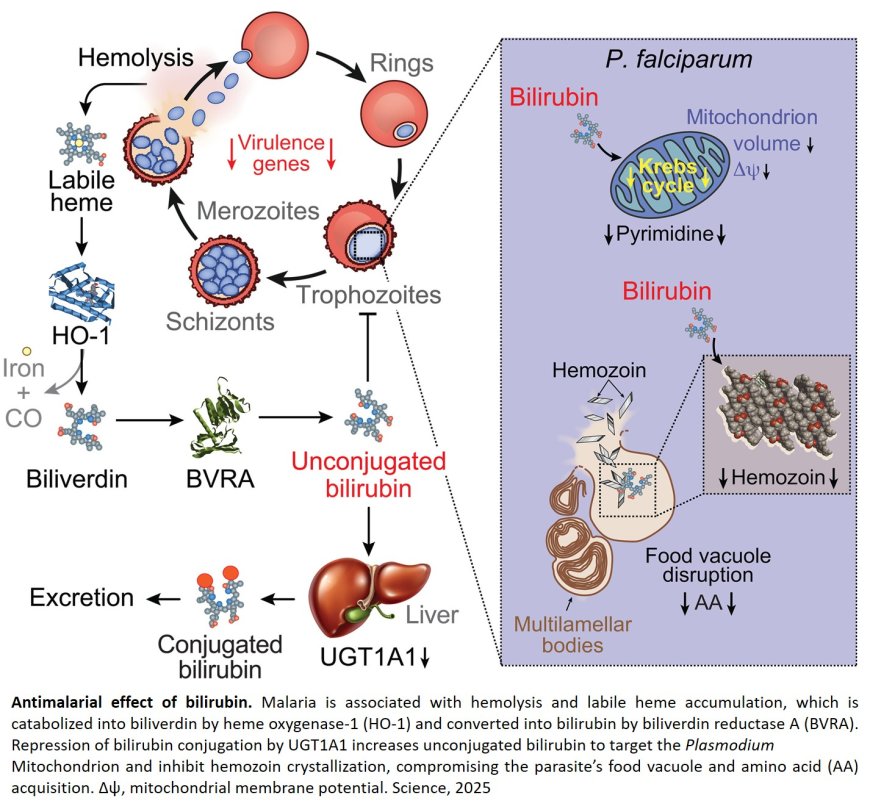

New research suggests that a pigment that causes yellowing of the skin, or jaundice, may help protect people from the most severe consequences of malaria. The report, which builds on a previous study on the protective role of bilirubin in the brain.

The parasitic disease, transmitted by the bites of some mosquitoes, is estimated to affect more than 260 million people a year in tropical and subtropical areas, and kills around 600,000 people annually, according to the World Health Organization.

The new research findings suggest bilirubin may be a potential target of drugs that boost its production to prevent malaria’s most deadly or debilitating effects, says the senior author of the study. Although bilirubin is one of the most commonly measured metabolites in the blood, the author says its roles in the body are only beginning to be understood.

A report on the findings was published in the journal Science.

Previous studies have identified the important role bilirubin plays in protecting brain cells from damage from oxidative stress. Although prior research from the lab had shown protective effects potentially related to bilirubin in people with malaria, the senior author says it was unclear whether the pigment protected or worsened the disease.

The mouse model and methods used to measure bilirubin in the new study were initially developed by the lab for the 2019 study.

Jaundice, or yellowing of the skin, is a common presentation of malaria, says the author, and anywhere from 2.5% to 50% of patients with malaria experience jaundice, according to two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine and Clinical Infectious Disease.

In a bid to pin down the role of bilirubin, the scientists conducted an analysis of blood samples taken with permission from a volunteer group of 42 patients who were infected with malaria parasite P. falciparum, which causes the deadliest form of the condition, according to the World Health Organization.

The authors further optimized method to measure bilirubin and its precursor biliverdin, the scientists measured the amount of bilirubin not yet processed by the liver in blood samples with both asymptomatic and symptomatic malaria. They found that, on average, people with asymptomatic malaria had 10 times more unprocessed bilirubin in the blood as symptomatic people, and suspected that accumulation of the pigment may have helped protect them from malaria.

Next, the researchers exposed normal mice and mice genetically engineered to lack BVRA, a protein that helps produce bilirubin, to a form of malaria that infects rodents.

Using the same methods, the researchers analyzed the rate at which the malaria parasite died off in both bilirubin-lacking mice and in normal mice.

In normal mice, the author says the concentration of unprocessed bilirubin in their systems increased significantly after they were infected with malaria, and all of the mice survived. In the mice lacking BVRA, the parasite spread vigorously, and all of the mice died.

The scientists then set out to test whether bilirubin could help BVRA-lacking mice overcome their infections, or whether it contributed to worsening symptoms. They gave bilirubin to malaria-infected mice that were also lacking BVRA, and saw that providing mice with higher doses of bilirubin resulted in survival times similar to that of normal mice.

The senior author plans to further study bilirubin in mice to determine the potential protective effect of the pigment in the brain.

“Bilirubin was once considered to be a waste product,” the author says. “This study affirms that it could be one critical protective measure against infectious disease, and potentially neurodegenerative diseases.”