Despite fewer animals, precise results in behavioral analysis

There is one specific task that stress researchers who conduct animal experiments need to be particularly skilled at. This also applies to researchers who want to improve the conditions in which laboratory animals are kept. They need to be able to assess the wellbeing of their animals based on behavioural observations, because unlike with humans, they cannot simply ask them how they are feeling. Researchers have now developed a method that significantly advances their analysis of mouse behaviour.

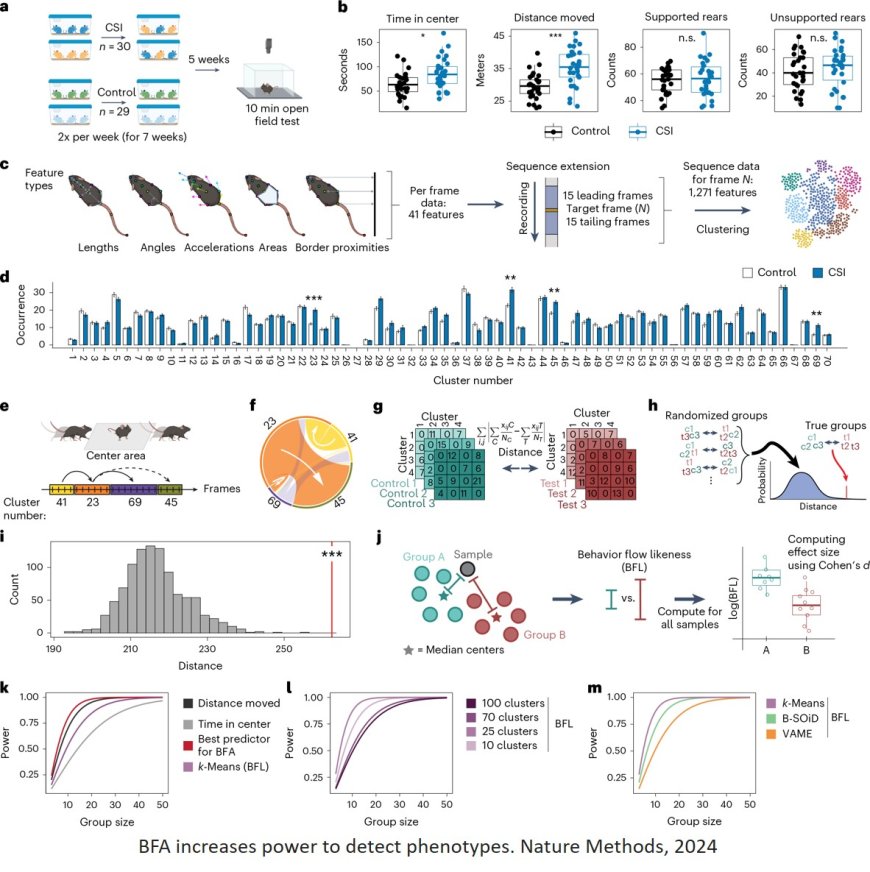

The process makes use of automated behavioural analysis through machine vision and artificial intelligence. Mice are filmed and the video recordings are analysed automatically. While analysing animal behaviour used to take many days of painstaking manual work – and still does in most research laboratories today – world-leading laboratories have switched to efficient automated behavioural analysis methods in recent years.

One problem this causes is the mountains of data generated. The more data and measurements available, and the more subtle the behavioural differences to be recognised, the greater the risk of being misled by artefacts. For example, these may include an automated process classifying a behaviour as relevant when it is not. Statistics presents the following simple solution to this dilemma – more animals need to be tested to cancel out artefacts and still obtain meaningful results.

The researchers’ new method now makes it possible to obtain meaningful results and recognise subtle behavioural differences between the animals even with a smaller group, which helps to reduce the number of animals in experiments and increase the meaningfulness of a single animal experiment. It therefore supports the 3R efforts made by various research institutions. The 3Rs stand for replace, reduce and refine, which means trying to replace animal experiments with alternative methods or reduce them through improvements in technology or experimental design.

The researchers’ method not only makes use of the many isolated, highly specific patterns of the animals’ behaviour; it also focuses closely on the transitions from one behaviour to another.

Some of the typical patterns of behaviour in mice include standing up on their hind legs when curious, staying close to the walls of the cage when cautious and exploring objects that are new to them when feeling bold. Even a mouse standing still can be informative – the animal is either particularly alert or uncertain.

The transitions between these patterns are meaningful – an animal that switches quickly and frequently between certain patterns may be nervous, stressed or tense. By contrast, a relaxed or confident animal often displays stable patterns of behaviour and switches between them less abruptly. These transitions are complex. To simplify them, the method mathematically combines them into a single, meaningful value, which render statistical analyses more robust.

The researcher said. “If we can use behavioural analyses to identify – or, even better, predict – how well an individual can handle stress, we can examine the specific mechanisms in the brain that play a role in this,” the author says. Potential therapy options for certain human risk groups might be derived from these analyses.

With the new method, the team has already been able to find out how mice respond to stress and certain medicines in animal experiments. Thanks to statistical wizardry, even subtle differences between individual animals can be recognised. For example, the researchers have managed to show that acute stress and chronic stress change the mice’s behaviour in different ways. These changes are also linked to different mechanisms in the brain.

The new approach also increases the standardisation of tests, making it possible to better compare the results of a range of experiments, even those conducted by different research groups.

“When we use artificial intelligence and machine learning for behavioural analysis, we are contributing to more ethical and more efficient biomedical research,” says the author. The team have been addressing the topic of 3R research for several years now. They have established the 3R Hub for this purpose. The Hub aims to have a positive influence on animal welfare in biomedical research.

“The new method is the 3R Hub’s first big success. And we’re proud of it,” says a co-author of this study. The 3R Hub now helps to make the new method available to other researchers. “Analyses like ours are complex and require extensive expertise,” explains the senior author. “Introducing new 3R approaches is often a major hurdle for many research laboratories.” This is precisely the idea behind the 3R Hub – enabling the spread of these approaches through practical support to improve animal welfare.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41592-024-02500-6

https://sciencemission.com/Analysis-of-behavioral-flow-resolves-latent-phenotypes