Mast cells’ role as gatekeepers against pathogens in brain

The itching, redness and swelling of an allergic reaction are caused by mast cells — the vigilant first responders of the immune system that spring into action with histamine-filled granules in response to a perceived threat.

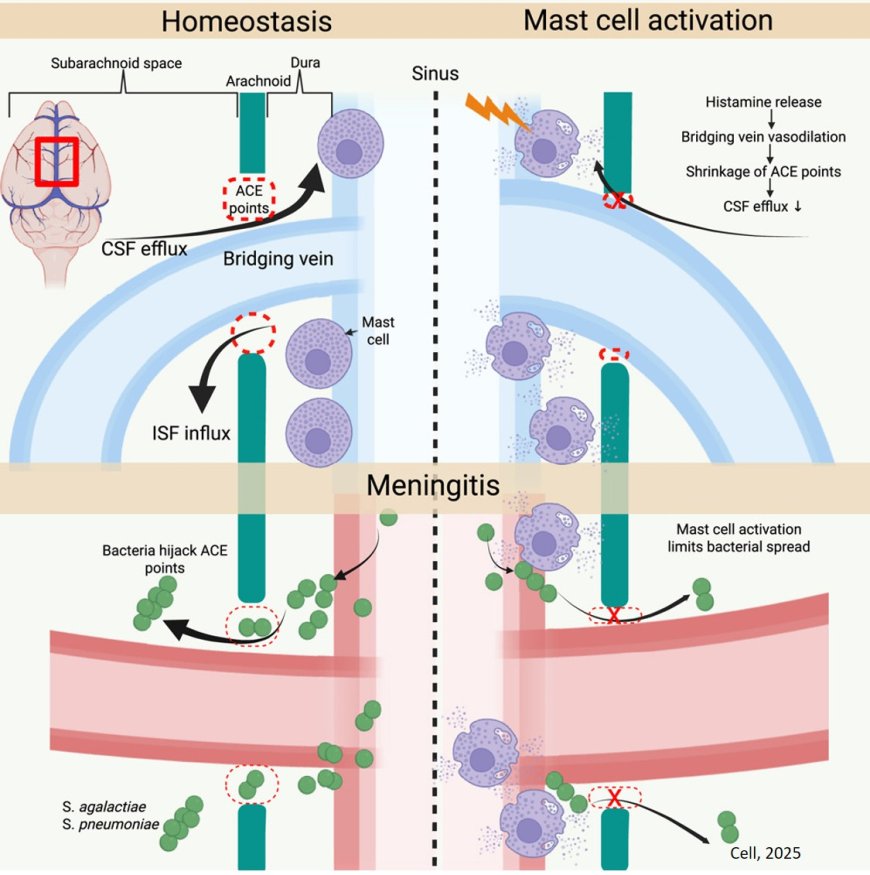

Now, researchers have revealed that the same cells that cause misery for millions of allergy sufferers can help protect the brain from bacterial and viral infections. In mice, they found that so-called mast cells stand guard at tiny gates through which fluid waste leaves the brain, mounting a response when a pathogen is detected to close the gates and prevent the invaders from accessing the brain.

The findings were published in Cell and could have important implications for preventing or treating brain infections.

“These findings open up an entirely new avenue to developing interventions that would protect the brain from infection,” explained the senior author. “We now know how mast cells shield the brain, so we can explore enhancing their function during the threat of infections.”

Such infectious diseases include bacterial meningitis, a potentially life-threatening infection that affects the tissue layers, called meninges, that envelop the brain underneath the skull. Tiny gates within these layers create passageways that carry fluid waste out of the brain into lymphatic vessels, where immune cells monitor the fluid for signs of danger or infection. But such openings also can provide opportunities for bacteria to infiltrate.

The lab had discovered the presence of lymph vessels in the mouse dura mater, the outer tissue layer enveloping the brain underneath the skull, into which brain fluid flows through tiny gates. They found that mice infected with Streptococcus agalactiae or S. pneumoniae, types of spherical bacteria that cause meningitis, had reduced brain fluid flow through the gates compared with healthy mice.

They discovered that the presence of bacteria in the tissues enveloping the mouse brain activated mast cells to release histamine-containing granules that caused veins that pass through the tiny gates to dilate, or widen. By expanding into the space that brain fluid ordinarily passes through, the enlarged veins created a temporary closure that also blocked bacteria from entering and infecting the brain.

The study found that activated mast cells also initiate a fast immune response, recruiting bacteria-engulfing immune cells called neutrophils to destroy the pathogens in the infected tissue. When mice in the study lacked mast cells, more bacteria got into the brain by passing through the tiny gates, the researchers found, whereas enhancing mast cells’ activity before an infection reduced the bacterial load.

The researchers also detected more West Nile virus, which spreads through the bite of an infected mosquito, in the brains of infected mice without mast cells compared with infected mice with mast cells.

“We think that enhancing mast cell function could help protect the brain from bacterial and viral infection,” said the author. “But mast cell activation is a double-edged sword. Long-term activation of these cells blocks fluid movement and can potentially cause junk, such as amyloid beta, to accumulate in the brain.”

In future work, the team aims to understand if chronic activation of mast cells could have negative implications for Alzheimer’s disease, which is characterized by an accumulation of amyloid beta.

“Mast cells have an important role to play in the brain,” said the first author on the study. “Understanding how to target their function at the gates to the brain to keep pathogens out while allowing waste to leave will be critical for optimizing brain health.”

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)00748-2

https://sciencemission.com/Mast-cells-regulate-the-brain-dura