Master copper regulator in Alzheimer’s disease

Formally known as Caenorhabditis elegans, the nematode is a favorite of neuroscientists seeking to identify and manipulate genes that impact neural signaling and health. In a new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers link the function of the worm gene swip-10 to the control of copper. While known for its use in electrical wiring, pots, pans and jewelry, copper also is a vital micronutrient that plays several essential roles in all cells, including those of the human brain.

“Copper is required for the function of mitochondria, the powerhouse of cells, and its production of the energy-storing molecule ATP, which fuels hundreds of vital body functions such as muscle contraction, digestion and heart function as well as the signaling of brain neurons that allows us to think and feel,” said the senior author. “Copper also helps protect cells from harmful molecules termed reactive oxygen species, or ROS, which in excess can damage proteins and DNA, ultimately driving cell death, including neurons that die in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.”

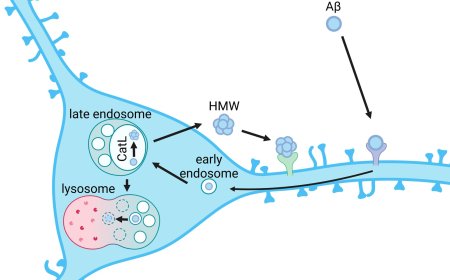

Copper exists mainly in two forms: cuprous copper (termed Cu(I)) and cupric copper (termed Cu(II)). These two forms are managed by different proteins in the body and can be converted from one to the other to support various chemical reactions vital to human health. Scientists are still studying how the body maintains the right balance between these two copper forms, which is important, as too much or too little of either can wreak havoc on cells, particularly neurons. This is where swip-10 enters the picture.

The team reported the identification of the swip-10 gene in 2015, following a screen for molecules needed to control the activity of worm dopamine neurons, specifically those that control their ability to swim.

“Worms with a damaging mutation in swip-10 initially swim normally, but unlike normal worms whose swimming continues for 30 minutes or more, in less than a minute, the mutants display swimming-induced paralysis or Swip,” said the author. “We tracked the paralysis to an excess activity of their dopamine neurons and published what we thought was a fairly complete story.”

But further studies by another past graduate student in the lab showed that the overactive dopamine neurons in swip-10 mutants exhibit degeneration much earlier in life than normal worms, as seen in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Other types of neurons in swip-10 mutant worms besides those making dopamine also demonstrate degeneration, suggesting to the team that links to brain disease might mirror other neurodegenerative disorders besides PD.

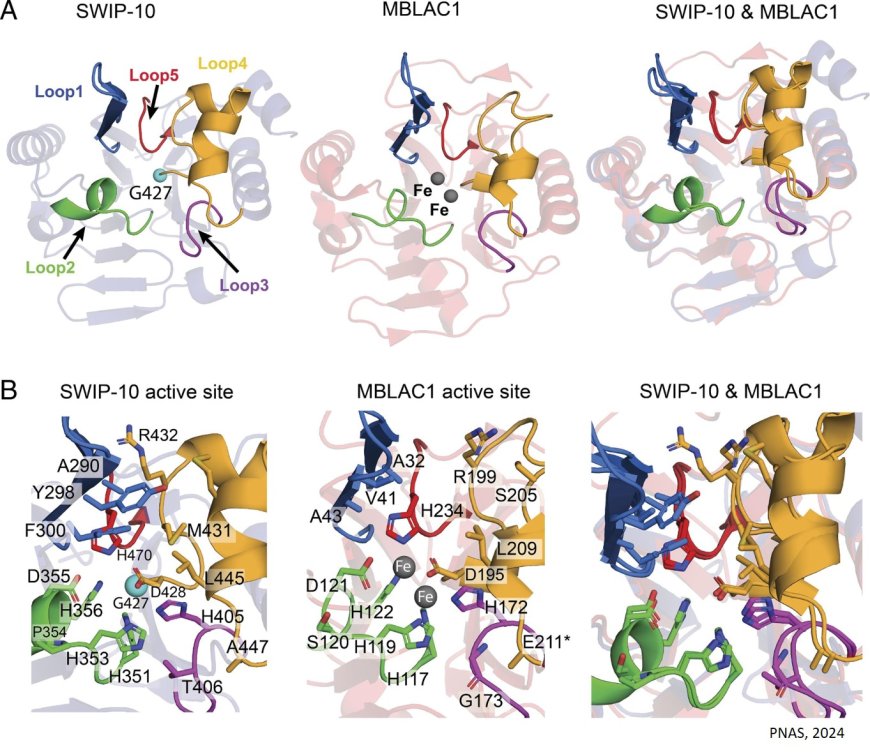

A clue to such disorders came with the decoding of the swip-10 gene sequence where the team found that humans possess a gene highly related to swip-10, termed MBLAC1. Then, in 2019, other researchers showed that MBLAC1 as a risk factor for a particular form of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one accompanied by cardiovascular disease (AD-CDV). Importantly, they also found a significant reduction in MBLAC1 expression in the frontal cortex of humans with AD-CDV, suggesting a role for MBLAC1 in supporting the health of both the brain and peripheral organs such as the heart. So where is the copper link?

“It turns out that MBLAC1 encodes an enzyme key to the production of another class of proteins, termed histones, well known to compact long strands of DNA so they can form chromosomes,” said the senior author.

But certain histones possess an additional, surprising activity, the ability to convert Cu(II) to Cu(I), and when mutations in these proteins were generated, these cells show much lower production of Cu(I), higher amounts of ROS, their mitochondria function poorly, and they fail to thrive.

Connecting the dots across the years, the lead scientist on the study reasoned that swip-10 mutants also would fail to produce the requisite histones, leading to a loss of Cu(I), mitochondrial dysfunction, and an elevation of ROS, which could be a major reason the worm’s dopamine neuron die. In the new study, the authors show that this is indeed the case, and moreover, find that they can rescue ATP production, reduce ROS, and promote survival of dopamine neurons by supplementing their diet with Cu(I) or by exposing them to a drug known to increase Cu(I) levels in cells.

“Surprisingly, the impact of loss of swip-10 on Cu(I), worm bioenergetics, and oxidative stress is not just an impact felt by dopamine neurons,” said the lead author. “Rather, Cu(I) levels, and these good things that Cu(I) does, are greatly diminished body-wide. Another striking finding is that though changes occur with Cu(I) and its actions across the body, these deficits arise from the loss of swip-10 from a small number of cells in the head of the animal known as glia, which make up only 5% of the cells in the animal’s body.”

Glial cells are well known to support the signaling and health of neurons in many organisms. Indeed, in the worm, the authors could restore the health of worms, as well as whole body Cu(I) levels, by expressing a normal copy of the swip-10 gene only in glial cells.

“The powerful control of Cu(I) exerted by swip-10 points to a novel opportunity to sustain neuronal health,” said the senior author.

Interestingly, the antibiotic ceftriaxone, which the Blakely lab found to bind MBLAC1 protein, has been reported by multiple groups to be neuroprotective in vitro and in animal models, though its mechanism of action is currently unclear. The team believes ceftriaxone’s action relates to modulating copper homeostasis.

“Ceftriaxone isn’t a particularly powerful drug, doesn’t get into the brain very well compared to other medications, and can cause antibiotic resistance and other side-effects. So it’s not surprising that it hasn’t proved useful in the clinic,” said the senior author. “Perhaps now that we have a better idea as to what swip-10 and MBLAC1 do, we think that we may be able to design a truly useful medication to treat neurodegenerative disease.”