Mechanism of adipocyte mechanoadaptation

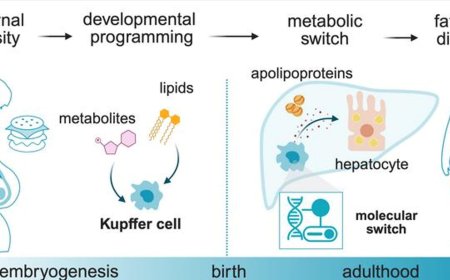

A team has identified an essential mechanism in fat cells (adipocytes) that enables them to enlarge safely to store energy. This process avoids tissue damage and protects the body from the toxic effects of accumulating fat molecules (lipids) in inappropriate places. The results, published in Nature Communications, signify a major advance in the understanding of metabolic diseases. Moreover, this discovery opens the door to the development of new therapeutic strategies to combat diseases related to chronic energetic excess, such as overweight, obesity, lipodystrophy, and metabolic syndrome, and their grave cardiovascular and metabolic complications.

In modern societies, characterized by sedentary lifestyles and high-calorie diets, adipose tissue is a key determinant of metabolic health. Adipocytes can enlarge to store energy in the form of fat, preventing excess lipids from accumulating in organs like the liver or in the blood vessel wall (especially in the heart and the brain), where they could cause irreparable damage.

Nevertheless, this process is not risk free. When adipocytes are overloaded with fat they can rupture, releasing their toxic contents and generating inflammation and metabolic alterations.

The study examined how adipocytes adapt to withstand the mechanical stress associated with their expansion to accommodate an excess of fat.

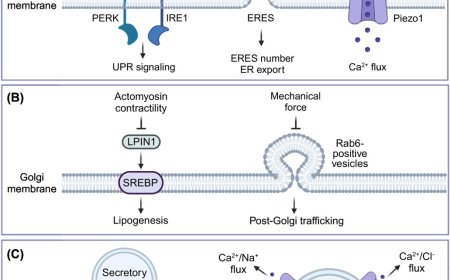

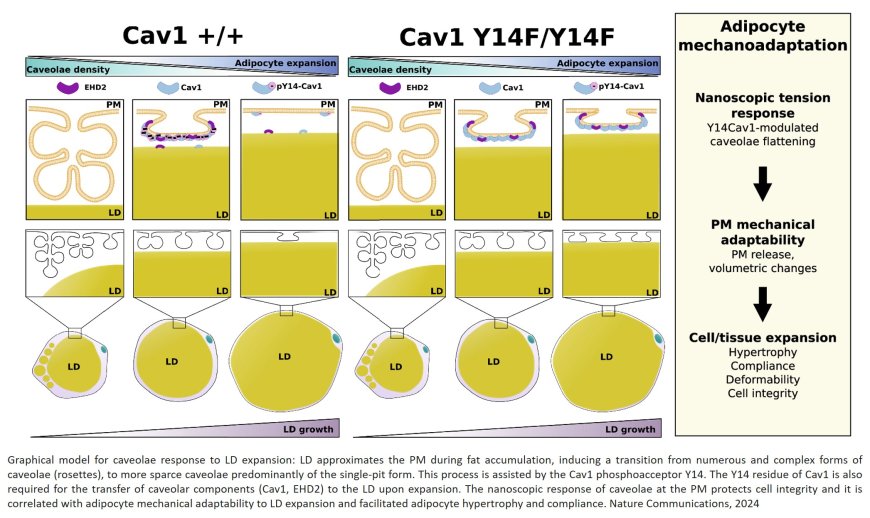

The team analyzed the role of caveolae, small invaginations in the cell membrane that act as sensors and shock absorbers of these stresses. “When an adipocyte accumulates fat and its surface is under increased tensile stress, the caveolae flatten, releasing a ‘reservoir’ of membrane that allows the cell to enlarge without breaking apart. Conversely, when fat reserves diminish, these structures regroup to reduce the excess membrane and restore cellular stability,” explained study first author.

As well as physically protecting adipocytes, caveolae also play an essential role in coordinating cell metabolism. The senior author explained that during adipocyte expansion, “molecular components of these membrane structures travel to other cell compartments, conveying signals that adjust metabolic activity to match the level of energy reserves. This capacity for internal communication makes caveolae key elements for efficient caveolar function.”

However, when these structures are absent or malfunction, adipocytes become more rigid, vulnerable to rupture, and less efficient at storing energy. The result, added the author, “is an inflammatory reaction that compromises the body’s metabolic health. This phenomenon is linked to conditions such as lipodystrophy, in which the body cannot store fat, leading to severe metabolic and cardiovascular alterations.”

The study highlights the key role of the caveolae protein caveolin-1 (Cav-1). For caveolae to flatten correctly in response to fluctuations in mechanical tension in the cell membrane, Cav-1 needs to be chemically altered by the addition of a phosphoryl group to a specific amino acid, a process called phosphorylation. For the study, the researchers developed a transgenic mouse that expresses a genetically altered version of Cav-1 that cannot be phosphorylated. This renders adipocytes unable to expand correctly in response to the mechanical tension generated by the accumulation of lipids, severely limiting their capacity to store energy and maintain cellular integrity. The failure of this simple mechanism ultimately leads to lipodystrophy and its severe consequences.

The author concluded that “these results give us a better understanding of how adipose tissue responds to the mechanical forces associated with energetic excess. In the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome, this protective mechanism is essential for minimizing organismal damage.”