Shapeshifting cancers’ masters, unmasked

Some tumors are almost impossible to treat. That’s especially true for carcinomas, which don’t behave like other malignancies. Some of these tumors act as shapeshifters and start to resemble cells from other organs of the human body, such as skin. This bizarre behavior presents a challenge for existing therapies.

“The tumors are notoriously plastic in their cellular identity,” says the senior author. Some may even change to escape cancer treatment.

Recent studies from the lab shine a new light on two hard-to-treat carcinomas, revealing vulnerabilities that could “tee up targets for therapy,” the author says.

In a study published in Nature Communications, the researchers identify a protein that determines whether pancreatic cancer cells maintain their classical form or begin to look and act more like skin cells. Meanwhile, in Cell Reports, they uncover the crystal structure of another group of proteins that plays a key role in tuft cell lung cancer.

This latest finding represents a full-circle moment for the lab, the author explains. When they discovered tuft cell lung cancer in 2018, they were searching for epigenetic factors that drive tumor growth. In other words, they were looking beyond the genes themselves and into the processes of transcription and gene regulation. Now, they’ve found what could someday become an epigenetic therapy designed to stop the cancer’s growth.

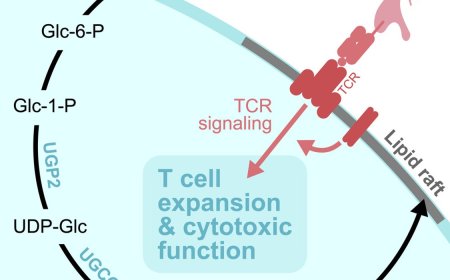

Tuft cells are defined by the transcription factor POU2F3 implicated in a subtype of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and its activity critically depends on the coactivators OCA-T1 and OCA-T2. The authors show that inhibition of either POU2F3 or OCA-T1 induces regression of tuft cell-like SCLC.

The authors determined crystal structures of POU2F3 bound to OCA-T1 or OCA-T2 in complex with DNA, revealing a tripartite, DNA-dependent interface. They identified mutation-sensitive hotspots and structurally constrained regions critical for tumor cell fitness.

“We aim to identify the master regulators of cellular identity,” the author says. The hope is that these “master regulators” could someday become the targets of new medicines, much like hormone therapies now used against breast and prostate cancers that were once difficult to treat. Of course, there’s still a long way to go.

Should the findings eventually lead to new drugs, the author hopes they will be engineered to target the cancer without harming other parts of the patient’s body. That ethos is apparent in both of his lab’s latest studies. Whether going after mouse models of pancreatic cancer or lung cancer, they see no evidence of toxicity or damage to vital organs. “We’re setting a higher bar for specificity when it comes to new cancer targets and treatments,” the senior author says.

https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(25)01344-0