Mapping centuries old genetic mutation that protects against HIV

What do a millennia-old human from the Black Sea region and modern HIV medicine have in common? Quite a lot, it turns out, according to new research.

The chemokine receptor variant CCR5delta32 is linked to HIV-1 resistance. 18-25 percent of the Danish population carries a genetic mutation that can make them resistant or even immune to HIV. This knowledge is used to develop modern treatments for the virus.

Until now, it was unknown where, when, or why the mutation occurred. But by using advanced DNA technology, researchers have now solved this genetic mystery.

“It turns out that the variant arose in one individual who lived in an area near the Black Sea between 6,700 and 9,000 years ago,” says the corresponding author of a new study mapping the mutation.

The author adds: “HIV is a relatively new disease – less than 100 years old – so it’s almost coincidental and very fascinating that a genetic variation that arose thousands of years ago also protects against a modern virus like HIV.”

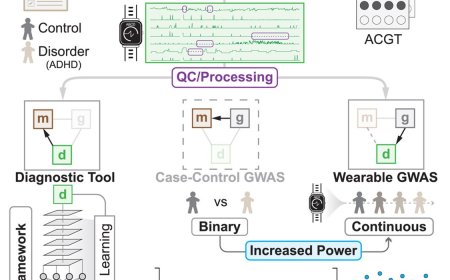

To determine where and when the mutation arose, researchers first mapped it by analyzing the genetic material of 2,000 living people worldwide. They then developed a new AI-based method to identify the mutation in ancient DNA from old bones.

The researchers examined data from over 900 skeletons dating from the early Stone Age to the Viking Age.

“By looking at this large dataset, we can determine where and when the mutation arose. For a period, the mutation is completely absent, but then it suddenly appears and spreads incredibly quickly. When we combine this with our knowledge of human migration at the time, we can also pinpoint the region where the mutation originated,” explains the first author.

Thus, the researchers were able to locate the mutation in a person from the Black Sea region up to 9,000 years ago – an individual from whom all carriers of the mutation descend.

But why do so many Danes carry a millennia-old genetic mutation that protects against a disease that didn’t exist back then?

The researchers believe the mutation arose and spread rapidly because it gave our ancestors an advantage:

“People with this mutation were better at surviving, likely because it dampened the immune system during a time when humans were exposed to new pathogens,” explains a co-first author.

The authors wrote: “What’s fascinating is that the variation disrupts an immune gene. It sounds negative, but it was likely beneficial. An overly aggressive immune system can be deadly – think of allergic reactions or severe cases of viral infections like COVID-19, where the immune system often causes the damage that kills patients. As humans transitioned from hunter-gatherers to living closely together in agricultural societies, the pressure from infectious diseases increased, and a more balanced immune system may have been advantageous.”