First human heart organoid to replicate A-fib

Though an estimated 60 million people around the world have atrial fibrillation, or A-fib, a type of irregular and often fast heartbeat, it’s been at least 30 years since any new treatments have been developed. This is because researchers haven’t had accurate models of the human heart to study. Thanks to new developments from scientists, that is no longer the case.

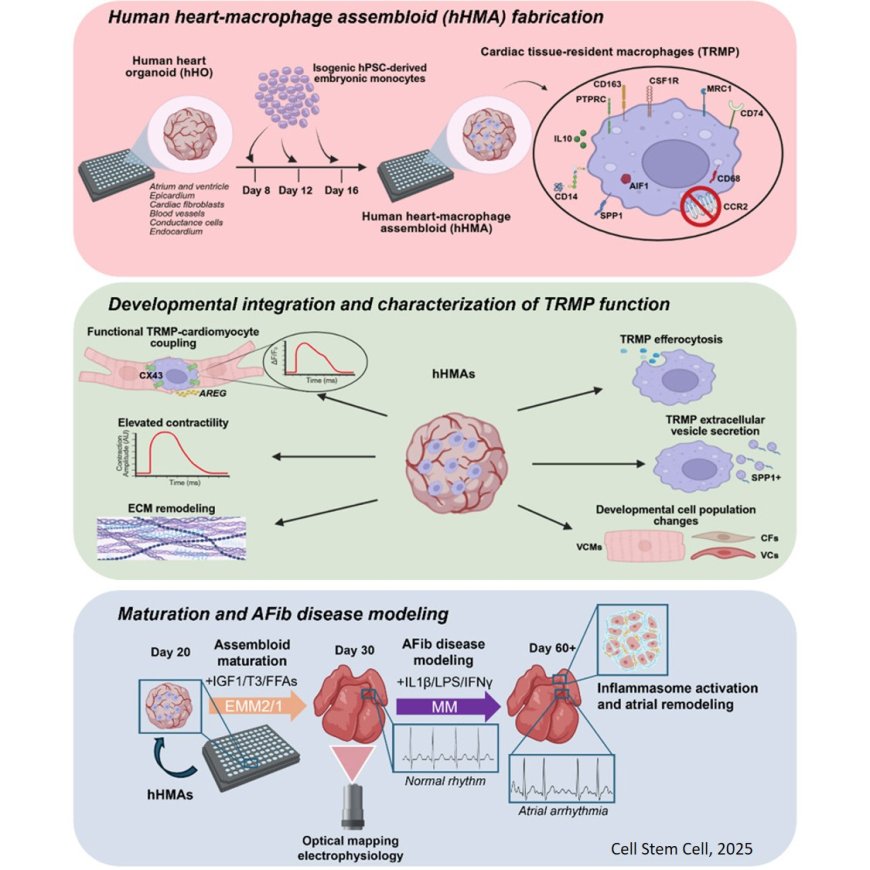

In 2020, MSU researcher Aitor Aguirre and his team started creating and perfecting tiny working models of the human heart known as organoids. Now, these organoids can be modified to replicate atrial fibrillation, or A-fib.

Roughly the size of a lentil, the three-dimensional heart organoids are so accurate that researchers can study heart development, diseases and drug responses in ways that were previously impossible. The organoids’ rhythmic beating is so strong that it can be seen without a microscope.

The team uses donated human stem cells, which can develop into many different types of cells and are crucial for growth and tissue repair throughout life, to develop the heart organoids. These organoids are truly mini hearts, complete with chamber-like structures and vascular networks including arteries, veins and capillaries.

The latest milestone from the lab comes when immune cells were added to the organoids. In developing human hearts, these immune cells, or macrophages, help ensure proper growth and formation.

The researchers were able to initiate inflammation in the organoids to cause an irregular heartbeat, which mimics A-fib. The findings are published in Cell Stem Cell.

“Our new model allows us to study living human heart tissue directly, something that hasn’t been possible before,” the author said. “When we added inflammatory molecules, the heart cells began beating irregularly. Then we introduced an anti-inflammatory drug, and the rhythm partially normalized. It was incredible to see that happen.”

No new drugs have been developed for A-fib in more than 30 years. This condition remains poorly treated because current therapies tend to target symptoms rather than underlying mechanisms. Therapeutic drug development for A-fib has struggled because there are no reliable animal models that resemble the disease.

“This new model can replicate a condition that is at the core of many people’s medical problems,” the senior author added. “It’s going to enable a lot of medical advances so patients can expect to see accelerated therapeutic developments, more drugs moving into the market, safer drugs and cheaper drugs, too, because companies are going to be able to develop more options.”

In the study, the researchers showed that long-lived, innate immune cells that reside in specific organs help guide the heart’s development and rhythm. This information also helps researchers understand the origins of congenital heart disorders, the most common birth defects in humans.

The researchers then took things one step further. They developed a system to age the organoids to resemble adult hearts by exposing them to the kind of inflammation that leads to A-fib.

To demonstrate how the new model can be used to test therapies for inflammation-driven heart conditions, the team introduced an anti-inflammatory drug that, based on the team’s findings, was predicted to treat A-fib. This restored the heart’s normal rhythm.

The senior author explained that the addition of immune cells makes the models more physiologically accurate than ever before.

“We’re now seeing how the heart’s own immune system contributes to both health and disease,” the author said. “This gives us an unprecedented view of how inflammation can drive arrhythmias and how drugs might stop that process.”

The lack of physiologically accurate human models and the inability to test on human hearts have limited the discovery of new therapies and drugs to treat arrhythmias like A-fib.

“Our new human heart organoid model is poised to end this 30-year drought without any new drugs or therapies,” said the senior author.

“Our longer-term vision is to develop personalized heart models derived from patient cells for precision medicine and to generate transplant-ready heart tissues one day,” the author said.

https://www.cell.com/cell-stem-cell/fulltext/S1934-5909(25)00367-4