How lysosome deals with stress

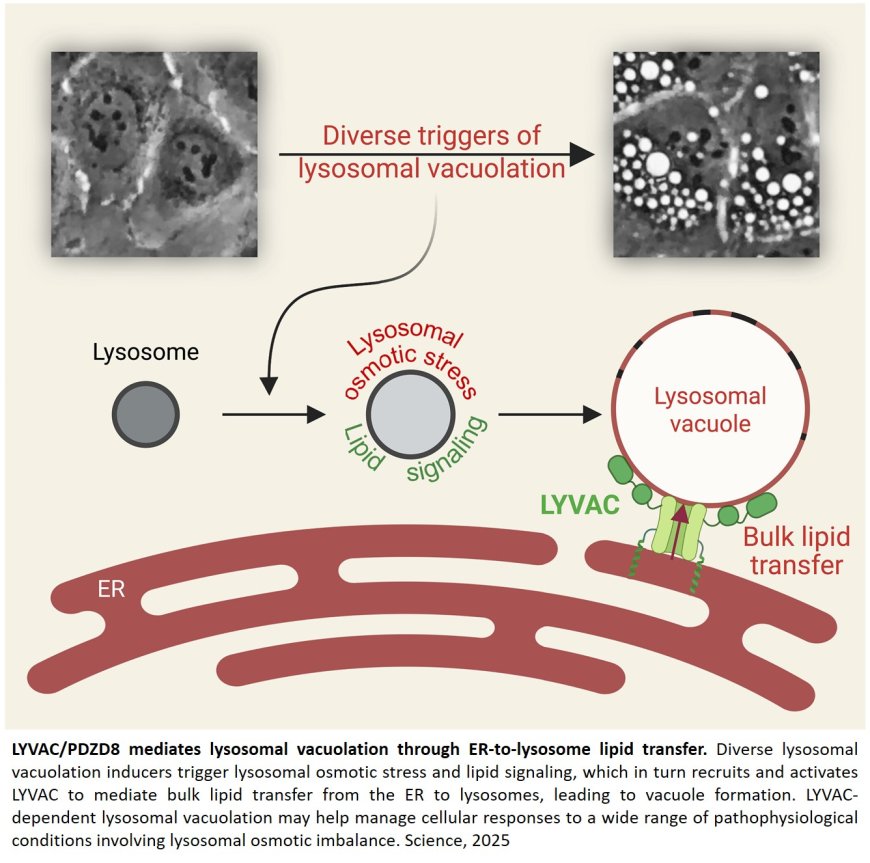

New research, published in the journal Science, shows how lysosomes — organelles that act like cells’ waste disposal system — respond to stress by becoming abnormally bloated, a process called lysosomal vacuolation that is associated with numerous diseases.

Essential for cellular health, well-functioning lysosomes are also linked with healthy aging, so better understanding of the steps involved in vacuolation could eventually inform new therapies to treat diseases or promote healthy aging, according to the senior author.

A vacuole is a membrane-bound compartment inside cells, like a water balloon, that stores water, molecules or waste. In plant cells, the central vacuole is large and helps store nutrients, regulate pressure and maintain structural rigidity. Animal cells don’t usually have vacuoles, but they contain related compartments called lysosomes. Lysosomal vacuolation refers to a condition in which lysosomes become abnormally enlarged like overinflated balloons, resembling plant vacuoles.

Lysosomes are essential for cell health. Like a waste disposal system, they digest damaged proteins, worn-out parts and invading microbes. By degrading a broad range of macromolecules, lysosomes preserve cellular function and longevity. Lysosomal vacuolation is thought to be an indication of stress or dysfunction of lysosomes, and these vacuoles are found in a large spectrum of medical conditions, including lysosomal storage disorders, aging, infection, chemotherapy, cataracts, cadmium toxicity, prion diseases and other neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

Lysosomal vacuolation has been observed in many diseases and has puzzled scientists for decades. However, it is still not known whether it is harmful or beneficial, largely because the mechanisms behind vacuole formation remain poorly understood. Without a molecular handle, it has not been possible to selectively remove these swollen lysosomes in order to test their physiological and pathological roles.

The researchers found that cells have a well-developed system to drive lysosomal vacuolation. In response to many different types of stress, lysosomes become filled up with solutes, which draws in water and stretches the lysosomal membrane — like inflating a balloon. The potential risk of lysosomal rupture is detected by a protein we named LYVAC, or lysosomal vacuolator.

LYVAC attaches to these stressed lysosomes, where it delivers lipids, which serve as membrane building blocks to allow lysosomal expansion in a controlled way. This process of lysosomal vacuolation is a natural, highly regulated response. LYVAC plays a central role in this process, helping cells adapt to stress and maintain lysosomal stability.

The cell seems to know exactly which lysosomes are in trouble and sends the protein LYVAC to help only those. LYVAC does two things: it sticks to the stressed lysosome and then helps move lipids to it so the membrane can grow and form a vacuole. Both steps need two separate signals to happen, which keeps everything precise and prevents LYVAC from acting on healthy parts of the cell. We didn’t expect this kind of accuracy, and it was really exciting to see.

By targeting LYVAC, one can understand the exact roles that lysosomal vacuoles play in different diseases. If vacuole formation turns out to be a key driver of disease, then blocking LYVAC could offer a promising new treatment strategy.

The authors continue to explore how LYVAC is controlled — what turns it on, and how it recognizes which lysosomes are under stress. They are also testing whether LYVAC is helpful or harmful in a genetic model of neurodegeneration, where large lysosomal vacuoles naturally appear.

The study suggest that cells have multiple lipid-based systems to respond to different types of lysosomal stress. By better understanding these processes, we hope to uncover new strategies to protect cells and promote healthy aging.