Observing synapses in action

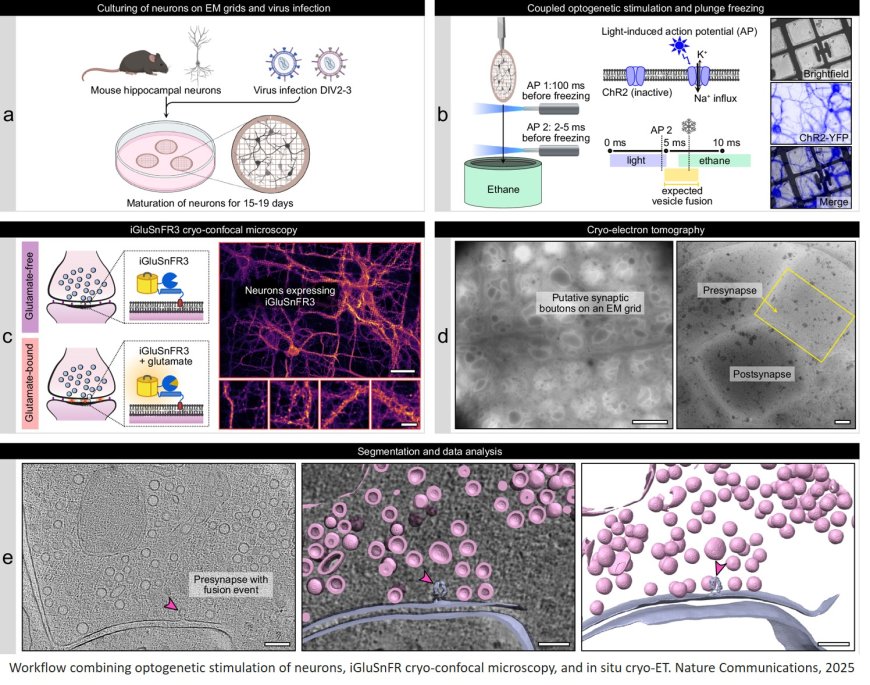

It takes just a few milliseconds: A vesicle, only a few nanometers in size and filled with neurotransmitters, approaches a cell membrane, fuses with it, and releases its chemical messengers into the synaptic cleft – making them available to bind to the next nerve cell. A research team has captured this critical moment of brain function in microscopic images. They describe their achievement in the journal “Nature Communications.”

“Until now, no one knew the exact steps of how synaptic vesicles fuse with the cell membrane,” says the first author of the study. “In our experiments with mouse neurons, we were able to show that initially, the process begins with the formation of a point-shaped connection. This tiny stalk then expands into a pore through which neurotransmitters enter the synaptic cleft,” the author explains.

“With technology we developed over five years, it was possible for the first time to observe synapses in action without disrupting them,” adds the senior author.

The images were produced at the CFcryo-EM (Core Facility for cryo-Electron Microscopy). The authors established a workflow for timed in situ cryo-electron tomography of optogenetically stimulated mouse neurons to capture the complete SV fusion sequence – from SV recruitment to fusion pore formation, opening and collapse.

To observe synapses in action, the team used mouse neurons genetically modified through optogenetics so they could be activated by a flash of light – prompting them to secrete neurotransmitters immediately. One to two milliseconds after a light pulse, the researchers flash-froze the neurons in liquid ethane at minus 180°C. “All cellular activity stops instantly with this ‘plunge freezing’ method, allowing us to visualize the structures using electron microscopy,” explains the author.

The method revealed another intriguing detail: “We found that most of the fusing vesicles were connected by tiny filaments to at least one other vesicle. As soon as one vesicle fuses with the membrane, the next one is already in position,” the author reports. “We believe that this direct form of vesicle recruitment enables neurons to send signals over a longer period of time and thus maintain their communication.”

The vesicle fusion process visualized by the team takes place millions of times a minute in the human brain. Understanding it in detail has important clinical implications. “In many people with epilepsy or other synaptic disorders, mutations have been found in proteins involved in vesicle fusion,” explains another author. “If we can clarify the precise role of these proteins, it will be easier to develop targeted therapies for these so-called synaptopathies.”

“The time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy approach using light, as we’ve presented here, isn’t limited to neurons,” the author adds. “It can be applied across many areas of structural and cell biology.”