Uncovering the secret of long-lived stem cells

Nothing lives forever, but compared to other cells in the body, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are remarkably long-lived. HSCs are blood-forming cells – they give rise to rapidly dividing progenitor cells, which in turn generate hundreds of billions of cells to fulfill the daily demand of oxygen-delivering red blood cells, disease-fighting white blood cells and clot-forming platelets.

HSCs typically remain dormant within the bone marrow, yet they possess the ability to activate and replenish blood cells continuously, maintaining a relatively youthful profile throughout the life of an organism. What is the secret of long-lived HSCs that wards off the effects of aging?

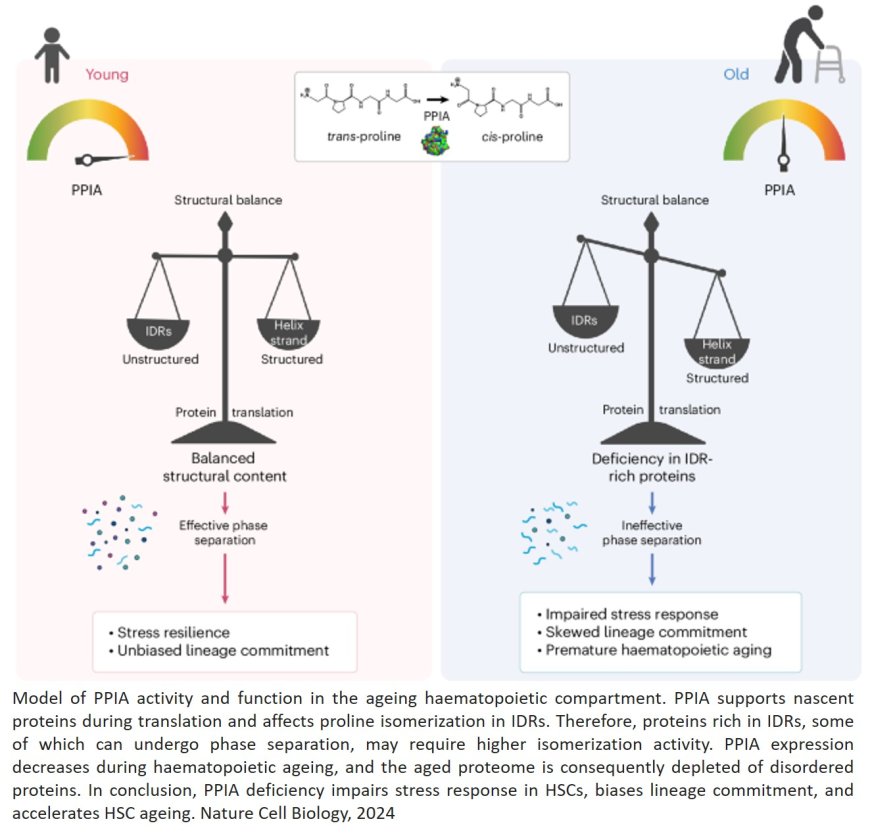

A team led by researchers revealed in Nature Cell Biology that the enzyme cyclophilin A, which is produced in large amounts in HSCs, is key for these cells to retain their regenerative potential and avert the effects of aging.

“A driving force of cellular aging is the accumulation of proteins that have reached the end of their useful life,” said the corresponding author. “With age, proteins tend to misfold, aggregate and accumulate inside the cell, which leads to toxic stress that can disrupt cell function.”

Cells that frequently engage in cell division, like progenitor cells, can dispose of protein aggregates through dilution. On the other hand, long-lived HSCs, which do not divide often, face the problem of the accumulation of misfolded proteins and subsequent toxic stress. Nevertheless, HSCs remain impervious to aging. How do they do it?

“Understanding the molecular mechanisms that contribute to HSC aging not only contributes to the field of normal HSC biology, but also may have significant clinical relevance for cancer treatment,” said co-first author of the work,

Previous studies have shown that mammalian cells express several hundreds of molecular chaperones, proteins that preserve or change the three-dimensional conformation of existing proteins. Cyclophilins (also called PPIA), one of the most abundant chaperones, have been implicated in the aging process. However, how they affect cellular proteins has not previously been studied.

Working with mice, the researchers first characterized the protein content of HSCs and discovered that cyclophilin A is a prevalent chaperone. Further experiments showed that the expression of cyclophilin A was significantly decreased in aged HSCs, and genetically eliminating cyclophilin A accelerated natural aging in the stem cell compartment. In contrast, reintroducing cyclophilin A into aged HSCs enhanced their function. Together, these findings support cyclophilin A as a key factor in the longevity of HSCs.

Next, the team investigated the proteins with which cyclophilin A interacts, preserving their stability. “We found that proteins enriched in intrinsically disordered regions are frequent targets of the chaperone,” the author said.

Intrinsically disordered proteins naturally change their 3-D conformation to interact with different proteins, nucleic acids or other molecules. Consequently, proteins rich in intrinsically disordered regions regulate many cellular processes by promoting specific activities between molecules. "Due to their flexible nature, intrinsically disordered proteins are inherently prone to aggregation. Cyclophilin A supports these proteins in fulfilling their functions and simultaneously prevents them from clumping," the author said.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that cyclophilin A interacts with intrinsically disordered proteins from the moment of their synthesis. “As these proteins are being made, cyclophilin A makes sure they keep the appropriate conformations and are maintained at sufficient levels,” The author said. “Genetic depletion of cyclophilin A results in stem cells distinctively lacking intrinsically disordered proteins.”

“For the first time, our study showed that producing disordered proteins and maintaining the structural diversity of the proteins in a cell plays a role in HSC aging,” the author said.