Vision plays a key role in sculpting brain development

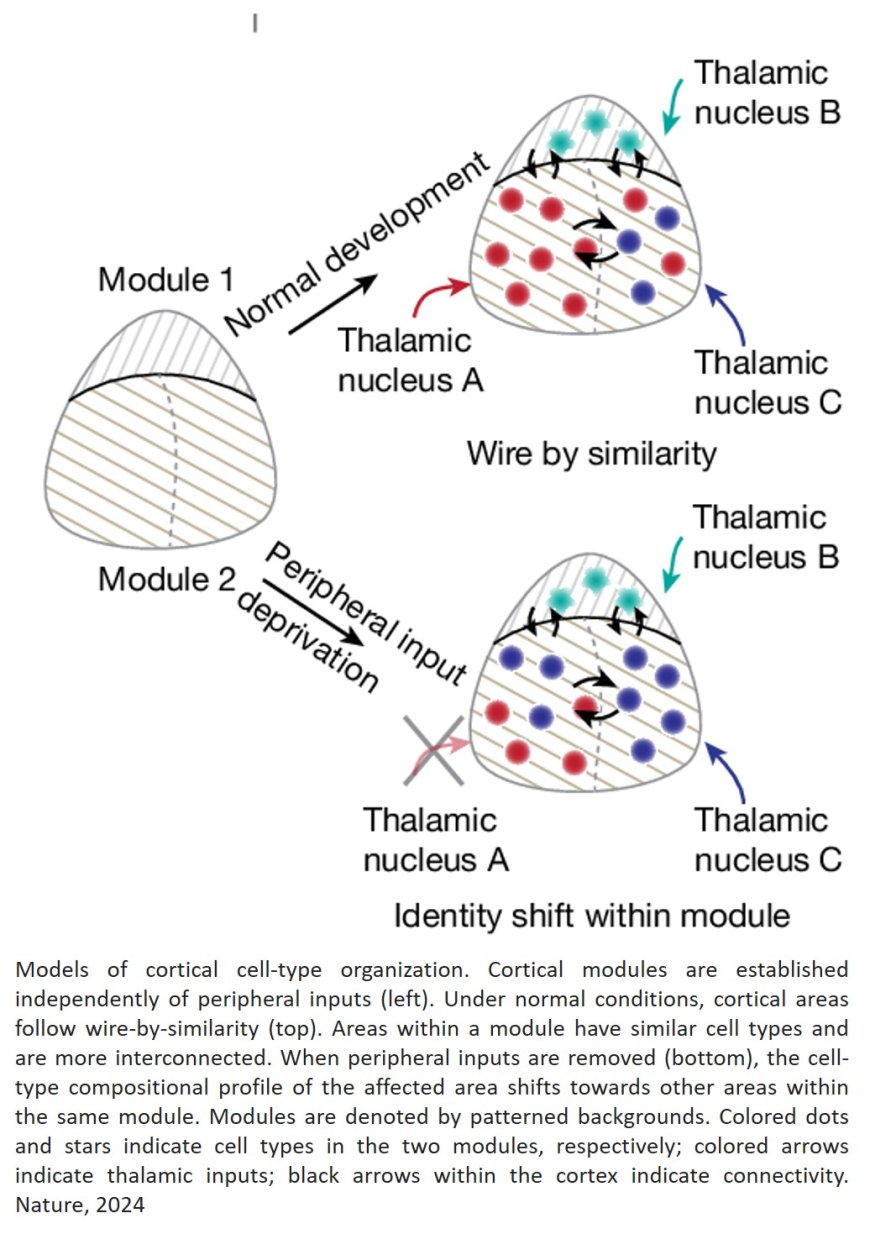

Scientists have long known that our brains are organized into specialized areas, each responsible for distinct tasks. The visual cortex processes what we see, for instance, while the motor cortex governs movement. But how these regions form—and how their neural building blocks differ—remain a mystery.

A study published in Nature sheds new light on the brain’s cellular landscape. Researchers used an advanced method called BARseq to swiftly classify and map millions of neurons across nine mouse brains. They discovered that while brain regions share the same types of neurons, the specific combination of these cells gives each area a distinct ‘signature,’ akin to a cellular ID card.

The team further explored how sensory inputs influence these cellular signatures. They discovered that mice deprived of sight experienced a major reorganization of cell types within the visual cortex, which blurred the distinctions with neighboring areas. These shifts were not confined to the visual area but occurred across half of cortical regions, though to a lesser extent.

The study underscores the pivotal role of sensory experiences in shaping and maintaining each brain region’s unique cellular identity.

“BARseq lets us see with unprecedented precision how sensory inputs affect brain development,” said the study’s co-lead author. “These broad changes illustrate how important vision is in shaping our brains, even at the most basic level.”

Previously, capturing single-cell data across multiple brains was challenging, said the other co-lead author. But BARseq is cheaper and less time-consuming than similar mapping technologies, the author said, enabling researchers to examine and compare brain-wide molecular architecture across multiple individuals.

BARseq tags individual brain cells with unique RNA ‘barcodes’ to track their connections across the brain. This data, combined with gene expression analysis, allows scientists to pinpoint and identify vast numbers of neurons in tissue slices.

For this study, the researchers used BARseq as a standalone method to rapidly analyze gene expression in intact tissue samples. In just three weeks, the researchers mapped more than 9 million cells from eight brains.

The scale and speed of BARseq provides scientists with a powerful new tool to delve deeper into the intricacies of the brain, the author said.

“BARseq allows us to move beyond mapping what a ‘model’ or ‘standard’ brain looks like and start to use it as a tool to understand how brains change and vary,” the author said. “With this throughput, we can now ask these questions in a very systematic way, something unthinkable with other techniques.”

The authors emphasized that the BARseq method is freely available. They hope their study encourages other researchers to use it to investigate the brain’s organizational principles or zoom in on cell types associated with disease.