p53 remodels 3D chromatin to trigger cellular stress response

The simplest explanation of cancer is that, for any reason, a cell in our body ignores its biological program and gets loose, multiplying itself again and again, creating a tumor. This has a lot to do with a wrong use of its genetic information, contained within its genes. Cells are smart enough to see this coming and try to activate an emergency response, usually through specific genes called tumor suppressors. The best-known of these is TP53 (producing the protein p53), discovered more than 40 years ago.

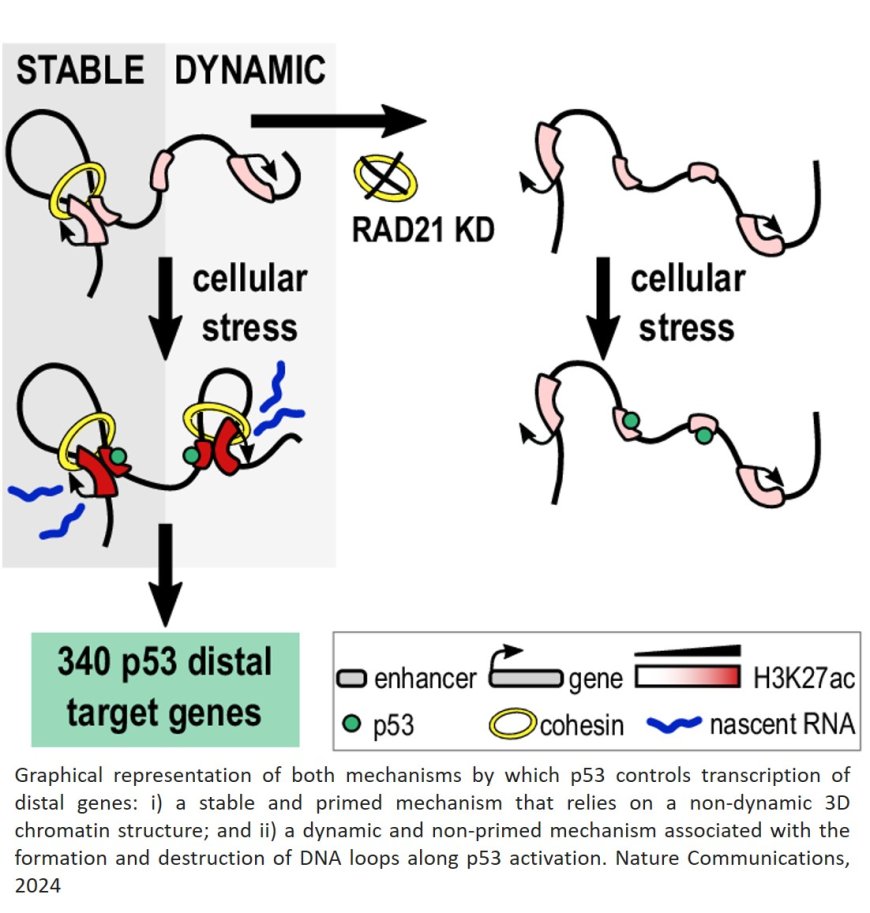

Scientists certainly know a lot about p53. It starts a broad cascade of events inside the cell, involving the activation of hundreds of other genes, that will collectively try to control damage or, as a last resort, kill the cell for the benefit of the organism. However, the direct effects of p53 right after its activation remained poorly understood and this is of utmost importance, since abnormal inactivation of p53 is a known hallmark of cancer progression.

The researchers developed an experimental setting able to detect the fast changes occurring as short as one hour after p53 activation and found it produced a heavy remodelling of the chromatin – the DNA inside the nucleus- consistent with the activation of its targets. The results were published in the journal Nature Communications.'

Overall, the study identified 340 p53 target genes being directly activated through long-range interactions, involving the contact of specific activation regions in the genome – enhancers - with the genes themselves. That’s why chromatin had to be physically reorganized within the nucleus. Noteworthy, 70% of the genes had not been previously linked with p53.

The team also proved that the rewiring of the chromatin was dependent on the presence of the cohesin complex, a known group of proteins in charge of stabilizing DNA loops, precisely the ones allowing the long-range interactions between enhancers and genes, strengthening their findings.

Despite being a key player in cancer suppression, very few therapeutical strategies have been directed towards restoring p53 function in tumors where it is inactivated, either directly or through its secondary targets. Perhaps, its newly reported mechanism of early action and the identification of many more genes under its control can inspire new approaches hitting the clinic in the future.