Biliverdin reductase A (BVRA) protects brain from oxidative stress damage

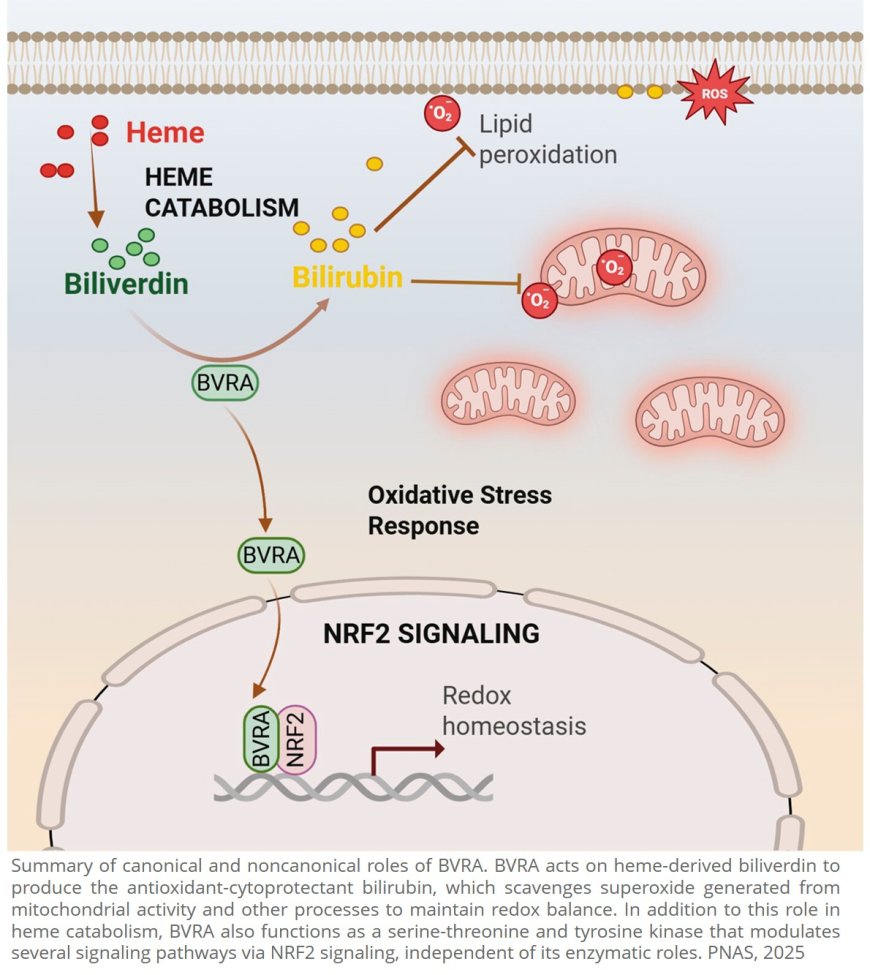

New research shows that the enzyme biliverdin reductase A (BVRA) plays a direct protective role against oxidative stress in neurons, independent of its role producing the yellow pigment bilirubin.

In this study of genetically engineered mice, the scientists say BVRA protected brain cells from oxidative stress, an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants that protect cells, by modulating another key protein, NRF2, which regulates the levels of protective proteins and antioxidants in cells. Oxidative stress is a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease.

A report describing the research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our research identifies BVRA as a key player in cellular defense with profound implications for aging, cognition and neurodegeneration,” says the senior author.

“This role of BVRA could potentially be targeted by drugs to slow the development of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease,” says a co-corresponding author.

The new research builds on past work published in Cell Chemical Biology that indicated how bilirubin serves as an antioxidant in the brains of mice. More recently, in a report published in Science, the pigment was shown to protect against the worst effects of malaria in mice.

In the recent study, scientists first genetically engineered mice to lack genes that make both BVRA and NRF2 proteins. However, none of these mice survived, indicating that together these proteins may have an important interaction.

Next, in mice genetically engineered to lack only BVRA, the scientists say NRF2 malfunctioned, and its target genes produced fewer antioxidants. In cell cultures, the team went on to show that BVRA and NRF2 physically bind, and in doing so regulate genes involved in protecting brain cells. The genes regulated by both proteins include those involved in transportation of oxygen, immune signaling and optimal functioning of mitochondria, the powerhouse of cells.

Importantly, this function did not require BVRA to produce bilirubin. Then, the team of scientists generated mutants of BVRA that could not make bilirubin. The scientists say these mutants retained their ability to regulate NRF2 and protected neurons in mice.

“This work shows that BVRA does more than produce bilirubin, and is actually a molecular integrator of key cellular processes that help protect neurons from damage,” says first author.

In future experiments, the authors aim to evaluate how the BVRA and NRF2 connection goes awry in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.