Brain-wide decision-making dynamics discovered

Neuroscientists have revealed how sensory input is transformed into motor action across multiple brain regions in mice. The research shows that decision-making is a global process across the brain that is coordinated by learning. The findings could aid artificial intelligence research by providing insights into how to design more distributed neural networks.

“This work unifies concepts previously described for individual brain areas into a coherent view that maps onto brain-wide neural dynamics. We now have a complete picture of what is happening in the brain as sensory input is transformed through a decision process into an action,” explained the corresponding author on the paper.

The study, published in Nature, outlines how the researchers used Neuropixels probes, a state-of-the-art technology enabling simultaneous recordings across hundreds of neurons in multiple brain regions, to study mice taking part in a decision-making task. The task allowed the team to distinguish between sensory processing and motor control. The researchers also revealed the contribution of learning through studying animals trained in the task and comparing them to naïve animals.

“We often make decisions based on ambiguous evidence. For example, when it starts to rain, you have to decide how high frequency the raindrops need to be before you open your umbrella. We studied this same ambiguous evidence integration in mice to understand how the brain processes perceptual decisions,” explained joint first author on the paper.

Mice were trained to stand still while they watched a visual pattern moving on a screen. To receive a reward, the mice had to lick a spout when they detected a sustained increase in the speed of movement of the visual pattern. The task was designed so that the speed of the movement was never constant, instead it continuously fluctuated. The timing of the increase in the average speed also changed from trial to trial so that the mice could not simply remember when the sustained increase occurred. Thus, the mice had to constantly pay attention to the stimulus and integrate information to work out whether the increase in the speed had happened.

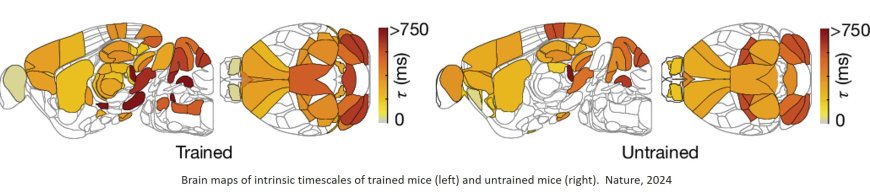

“By training the mice to stand still, the data analysis we could perform was much cleaner and the task allowed us to look at how neurons track random fluctuations in speed before the mice made an action. In trained mice, we found that there is no single brain region that integrates sensory evidence or orchestrates the process. Instead, we found neurons that are sparsely but broadly distributed across the brain link sensory evidence and action initiation,” explained another joint first author on the paper.

The researchers recorded from each mouse multiple times and collected data from over 15,000 cells across 52 brain regions in 15 trained mice. To look at learning, the team also compared the results to recordings from naïve mice.

“We found that when mice don’t know what the visual stimulus means, they only represent the information in the visual system in the brain and a few midbrain regions. After they have learned the task, cells integrate the evidence all over the brain,” explained the author.

In this study, the team only looked at naïve animals and those that had fully learned the task, but in future work they hope to uncover how the learning process occurs by tracking neurons over time to see how they change as mice begin to understand the task. The researchers are also looking to explore whether specific areas in the brain act as causal hubs in establishing these links between sensations and actions.

A number of additional questions raised by the study include how the brain incorporates an expectation of when the speed of visual pattern will increase such that animals only react to the stimulus when the information is relevant. The team plan to study these questions further using the dataset they have collected.