Cellular traffic congestion in chronic diseases

Chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes and inflammatory disorders have a huge impact on humanity. They are a leading cause of disease burden and deaths around the globe, are physically and economically taxing, and the number of people with such diseases is growing.

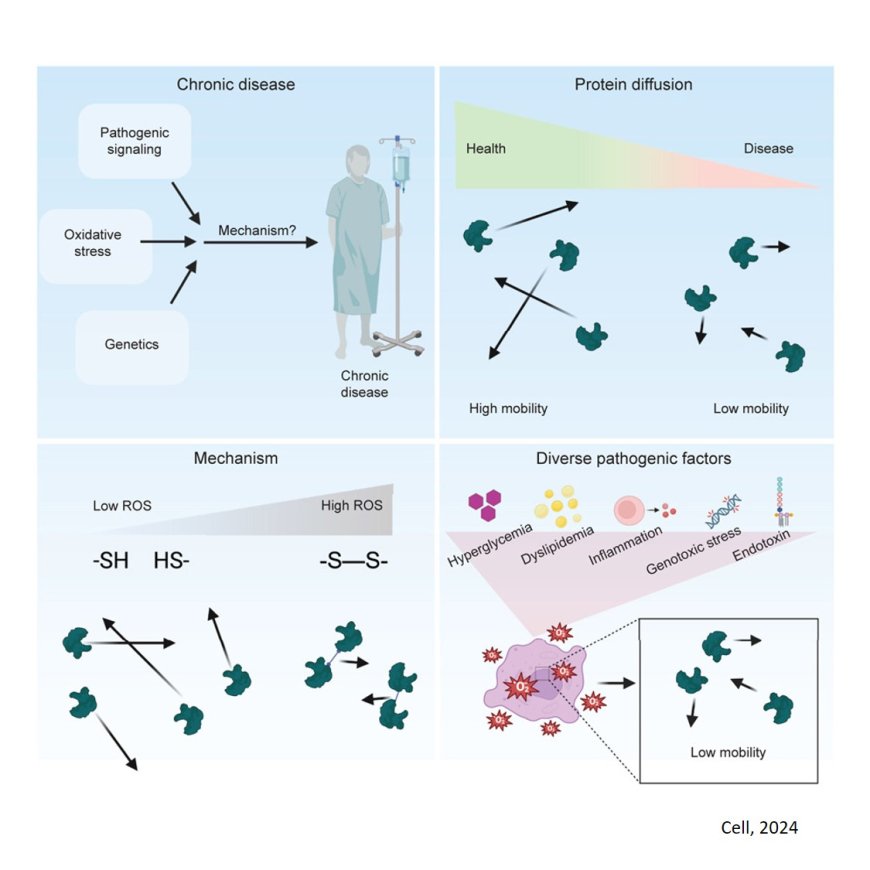

Treating chronic disease has proven difficult because there is not one simple cause, like a single gene mutation, that a treatment could target. At least, that’s how it has appeared to scientists. However, research published in the journal Cell, reveals that many chronic diseases have a common denominator that could be driving their dysfunction: reduced protein mobility. What this means is that around half of all proteins active in cells slow their movement when cells are in a chronic disease state, reducing the proteins’ functions. The researchers’ findings suggest that protein mobility may be a linchpin for decreased cellular function in chronic disease, making it a promising therapeutic target.

In this paper, the researchers describe their discovery of this common mobility defect, which they call proteolethargy; explain what causes the defect and how it leads to dysfunction in cells; and propose a new therapeutic hypothesis for treating chronic diseases.

“I’m excited about what this work could mean for patients,” says the author. “My hope is that this will lead to a new class of drugs that restore protein mobility, which could help people with many different diseases that all have this mechanism as a common denominator.”

How do proteins moving more slowly through a cell lead to widespread and significant cellular dysfunction? The author explains that every cell is like a tiny city, with proteins as the workers who keep everything running. Proteins have to commute in dense traffic in the cell, traveling from where they are created to where they work. The faster their commute, the more work they get done. Now, imagine a city that starts experiencing traffic jams along all the roads. Stores don’t open on time, groceries are stuck in transit, meetings are postponed. Essentially all operations in the city are slowed.

The slow down of operations in cells experiencing reduced protein mobility follows a similar progression. Normally, most proteins zip around the cell bumping into other molecules until they locate the molecule they work with or act on. The slower a protein moves, the fewer other molecules it will reach, and so the less likely it will be able to do its job. The authors found that such protein slow-downs lead to measurable reductions in the functional output of the proteins. When many proteins fail to get their jobs done in time, cells begin to experience a variety of problems—as they are known to do in chronic diseases.

The researchers first suspected that cells affected in chronic disease might have a protein mobility problem after observing changes in the behavior of the insulin receptor, a signaling protein that reacts to the presence of insulin and causes cells to take in sugar from blood. In people with diabetes, cells become less responsive to insulin — a state called insulin resistance — causing too much sugar to remain in the blood. In research published on insulin receptors in Nature Communications in 2022, the researchers reported that insulin receptor mobility might be relevant to diabetes.

Knowing that many cellular functions are altered in diabetes, the researchers considered the possibility that altered protein mobility might somehow affect many proteins in cells. To test this hypothesis, they studied proteins involved in a broad range of cellular functions, including MED1, a protein involved in gene expression; HP1α, a protein involved in gene silencing; FIB1, a protein involved in production of ribosomes; and SRSF2, a protein involved in splicing of messenger RNA. They used single-molecule tracking and other methods to measure how each of those proteins moves in healthy cells and in cells in disease states. All but one of the proteins showed reduced mobility (about 20-35%) in the disease cells.

Next, the researchers needed to determine what was causing the proteins to slow down. They suspected that the defect had to do with an increase in cells of the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), molecules that are highly prone to interfering with other molecules and their chemical reactions. Many types of chronic-disease-associated triggers, such as higher sugar or fat levels, certain toxins, and inflammatory signals, lead to an increase in ROS, also known as an increase in oxidative stress. The researchers measured the mobility of the proteins again, in cells that had high levels of ROS and were not otherwise in a disease state, and saw comparable mobility defects, suggesting that oxidative stress was to blame for the protein mobility defect.

The final part of the puzzle was why some, but not all, proteins slow down in the presence of ROS. SRSF2 was the only one of the proteins that was unaffected in the experiments, and it had one clear difference from the others: its surface did not contain any cysteines, an amino acid building block of many proteins. Cysteines are especially susceptible to interference from ROS because it will cause them to bond to other cysteines. When this bonding occurs between two protein molecules, it slows them down because the two proteins cannot move through the cell as quickly as either protein alone.

About half of the proteins in our cells contain surface cysteines, so this single protein mobility defect can impact many different cellular pathways. This makes sense when one considers the diversity of dysfunctions that appear in cells of people with chronic diseases: dysfunctions in cell signaling, metabolic processes, gene expression and gene silencing, and more. All of these processes rely on the efficient functioning of proteins—including the diverse proteins studied by the researchers. The authors performed several experiments to confirm that decreased protein mobility does in fact decrease a protein’s function. For example, they found that when an insulin receptor experiences decreased mobility, it acts less efficiently on IRS1, a molecule to which it usually adds a phosphate group.

Discovering that decreased protein mobility in the presence of oxidative stress could be driving many of the symptoms of chronic disease provides opportunities to develop therapies to rescue protein mobility. In the course of their experiments, the researchers treated cells with an antioxidant drug—something that reduces ROS—called N-acetyl cysteine and saw that this partially restored protein mobility.

The researchers are pursuing a variety of follow ups to this work, including the search for drugs that safely and efficiently reduce ROS and restore protein mobility. They developed an assay that can be used to screen drugs to see if they restore protein mobility by comparing each drug’s effect on a simple biomarker with surface cysteines to one without. They are also looking into other diseases that may involve protein mobility, and are exploring the role of reduced protein mobility in aging.

“The complex biology of chronic diseases has made it challenging to come up with effective therapeutic hypotheses,” says the senior author. “The discovery that diverse disease-associated stimuli all induce a common feature, proteolethargy, and that this feature could contribute to much of the dysregulation that we see in chronic disease, is something that I hope will be a real game changer for developing drugs that work across the spectrum of chronic diseases.