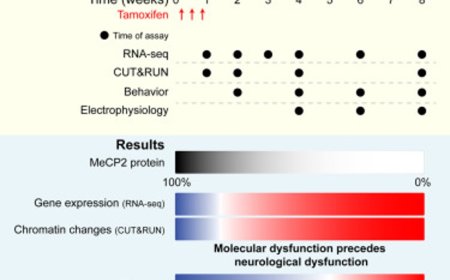

Early smell problem associated with Alzheimer’s linked to Locus Coeruleus noradrenergic axon loss

A fading sense of smell can be one of the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease even before cognitive impairments manifest. Research sheds new light on this phenomenon, pointing to a significant role for the brain’s immune response, which seems to fatally attack neuronal fibers crucial for the perception of odors.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, is based on observations in mice and humans, including analysis of brain tissue and so-called PET scanning. These findings may help to devise ways for early diagnosis and, consequently, early treatment.

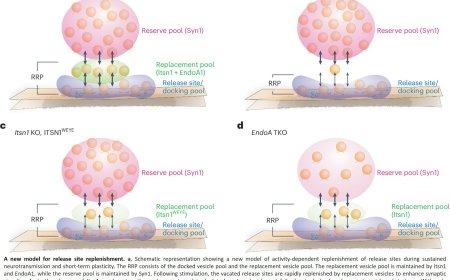

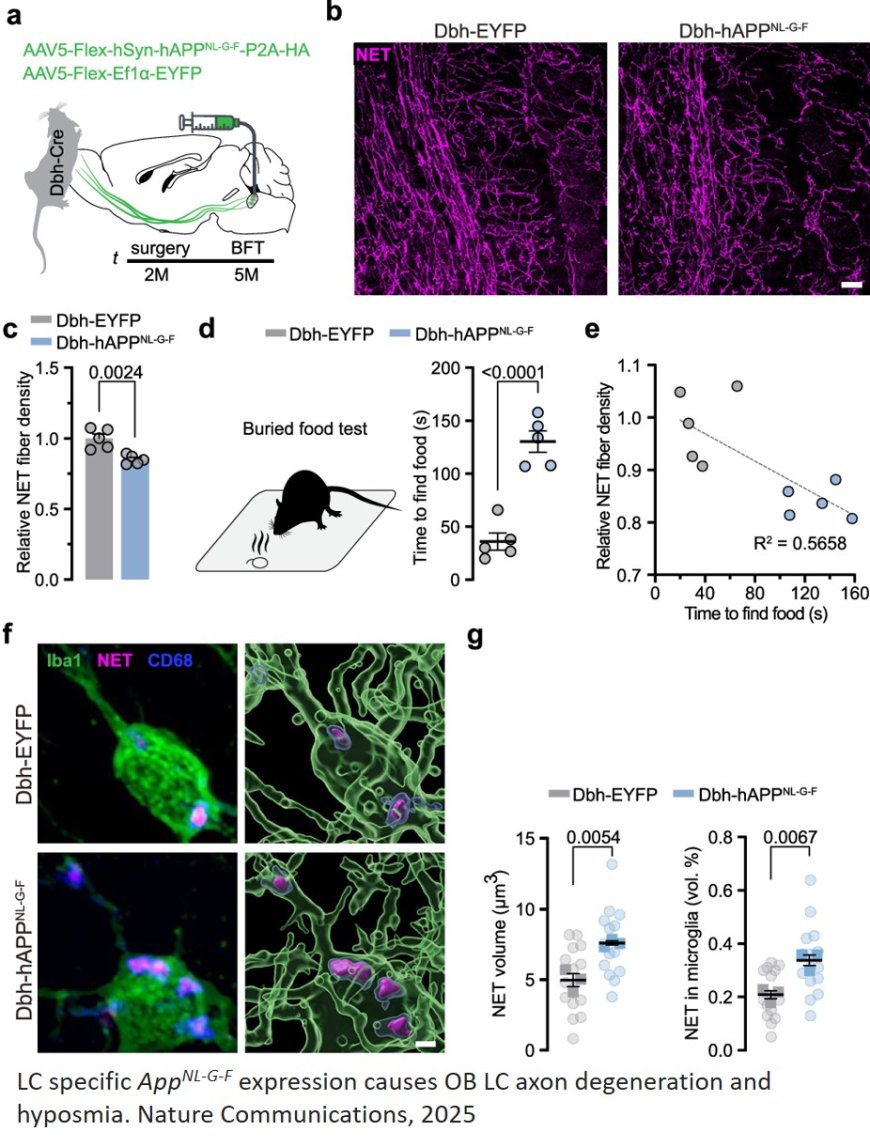

The researchers come to the conclusion that these olfactory dysfunctions arise because immune cells of the brain called “microglia” remove connections between two brain regions, namely the olfactory bulb and the locus coeruleus. The olfactory bulb, located in the forebrain, analyzes sensory information from the nose’s scent receptors. The locus coeruleus, a region of the brainstem, influences this processing by means of long nerve fibers originating from neurons in the locus coeruleus and extending all the way to the olfactory bulb.

“The locus coeruleus regulates a variety physiological mechanisms. These include, for example, cerebral blood flow, sleep-wake cycles, and sensory processing. The latter applies, in particular, also to the sense of smell,” says the author. “Our study suggests that in early Alzheimer’s disease, changes occur in the nerve fibers linking the locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb. These alterations signal to the microglia that affected fibers are defective or superfluous. Consequently, the microglia break them down.”

Specifically, the team found evidence of changes in the composition of the membranes of the affected nerve fibers: Phosphatidylserine, a fatty acid that usually occurs inside a neuron’s membrane, had been moved to the outside.

“Presence of phosphatidylserine at the outer site of the cell membrane is known to be an “eat-me” signal for microglia. In the olfactory bulb, this is usually associated with a process called synaptic pruning, which serves to remove unnecessary or dysfunctional neuronal connections”, explains the author. “In our situation, we assume that the shift in membrane composition is triggered by hyperactivity of the affected neurons due to Alzheimer’s disease. That is, these neurons exhibit abnormal firing.”

The findings are based on a plethora of observations. These include studies on mice with features of Alzheimer’s disease, analysis of brain samples from deceased Alzheimer’s patients, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans of the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s or mild cognitive impairment.

“Smell issues in Alzheimer's disease and damage to the associated nerves have been discussed for some time. However, the causes were unclear until yet. Now, our findings point to an immunological mechanism as cause for such dysfunctions – and, in particular, that such events already arise in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” says the research group leader.

So-called amyloid-beta antibodies have recently become available for the treatment of Alzheimer’s. For this novel therapy to be effective, it needs to be applied at an early stage of the disease, and this is precisely where the current research could be significant.

“Our findings could pave the way for the early identification of patients at risk of developing Alzheimer’s, enabling them to undergo comprehensive testing to confirm the diagnosis before cognitive problems arise. This would allow earlier intervention with amyloid-beta antibodies, increasing the probability of a positive response,” says the author.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-62500-8

https://sciencemission.com/Locus-Coeruleus-noradrenergic-axon-loss-in-AZ