Social lifetime experiences have long-lasting effects on mental and brain health

Lifetime significant experiences, in particular the social ones, are the fabric of our identity. But what about their impact in our health? Hardships of childhood, access to education quality and social networks, exposure to violence, and many other social domains may slowly accumulate over time and decades later may shape how the brain growth, connects, and copes.

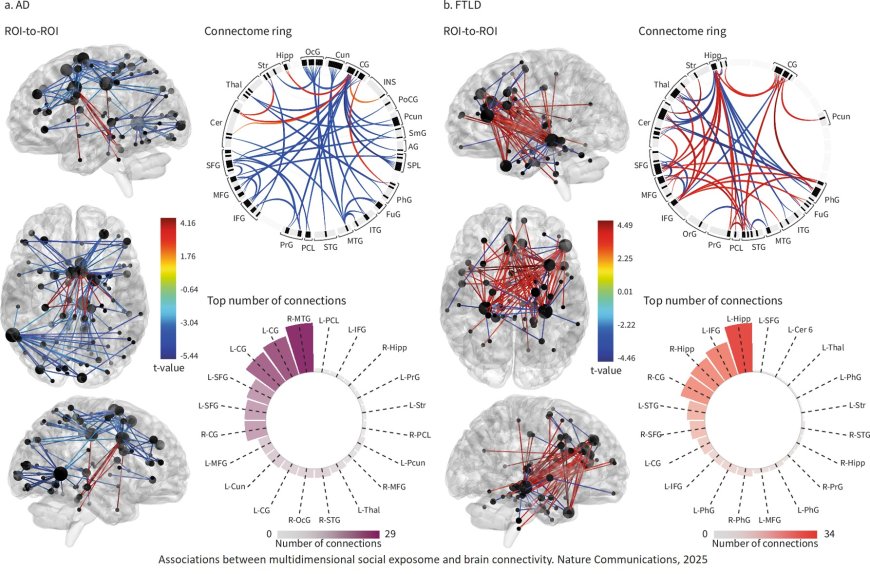

In a new groundbreaking work published in Nature Communications, researchers found that an adverse social exposome, defined as the cumulative exposure to factors such as low education, adverse childhood experiences, food insecurity, financial stress and assets, low access to healthcare, and traumatic events, is linked to poorer cognition and mental health, reduced functional ability, and alterations in brain structure and function. These effects have long-lasting impact not only in healthy aging but also in people living with dementia. This work suggests that healthy ageing dementia prevention should begin in childhood.

The researchers first created and validated an assessment of social exposome assessing 319 dimensions for education, food insecurity, financial status, assets, healthcare access, childhood labor, subjective and objective socioeconomic status, childhood experiences, traumatic events, and relationships. These scores were evaluated 2211 individuals (controls, Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration) from six Latin American countries. This region was chosen given the larger influence of social exposome. Structural inequality, educational disparities, and social determinants of health are impacting Latin Americans’ health.

In brief, the more adverse the social exposome, the larger the cognitive, functional, mental and brain impairments. Diverse social and environmental factors at different stages of life were associated with multiple dimensions of brain health. Adverse exposomes associated with poorer cognition in healthy ageing. In dementia, more complex exposomes (food insecurity, financial status, socioeconomic status, and access to healthcare) correlated with lower cognitive and functional performance, higher mental health symptoms, and brain structural and connectivity. More importantly, the accumulation of these exposures across the lifespan, rather than the impact of individual components assessed in isolation, showed the strongest associations. The variations in participants’ country of origin, demographic and dementia-related factors, image acquisition methods, or signal quality did not account for the results. Together, findings highlight how compounded social adversity becomes biologically embedded in brain structure and function. The tailored modeling of social exposome capture precise brain health outcomes of aging and dementia.

Dementia prevention should not only focus on a midlife action such as controlling hypertension or diabetes. It should begin in childhood, when the foundations of brain development are laid. Reducing food insecurity, improving education quality, and ensuring reliable access to healthcare and supportive environments in early and midlife can build brain health capital that pays off decades later.

The first author, said: “The interaction between modifiable risk factors and the social exposome offers a path toward developing precision dementia prevention agendas tailored to each individual’s social exposome and risk profile.”

The lead and corresponding author said: “a systematic association of the multidimensional social lifespan experiences on brain health outcomes. These results call for the development of tailored models incorporating the impact of lifespan social environments in the biological embedding of aging and dementia.”