Vasopressin, a neuropeptide, regulates both sociability and social aggression

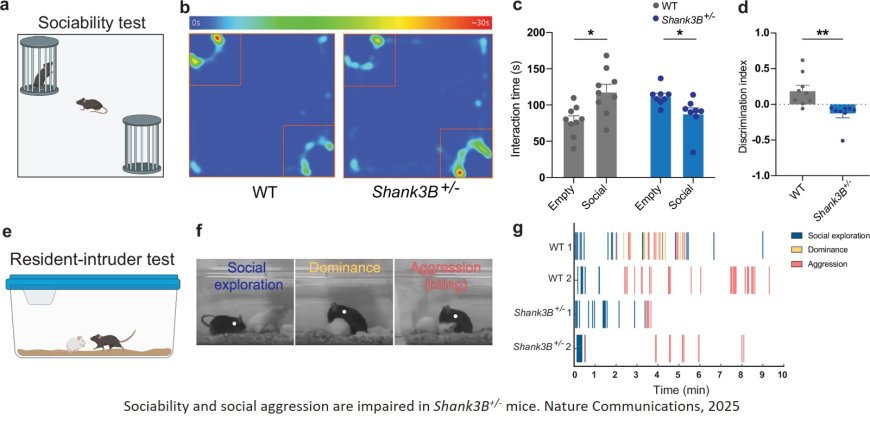

The researchers have identified for the first time the mechanism linking a mutation in the Shank3 gene with alterations in social behavior. Using a mouse model carrying this autism-associated mutation, the study shows that vasopressin, a brain hormone essential for social relationships, is not properly released in the lateral septum.

The work, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates that the proper release of vasopressin in this region regulates social behaviors through two distinct receptor pathways: one controlling sociability and the other controlling social aggression, and that selective activation of these receptors can reverse deficits in social interaction without triggering unwanted aggressive responses.

The findings provide the first detailed explanation of how a genetic mutation linked to autism leads to problems in social interaction. Until now, the Shank3 gene had been associated with the disorder, but the biological mechanism underlying this connection remained unclear. The key, as this study demonstrates, lies in vasopressin: a brain hormone that acts as a messenger between neurons and is essential for regulating sociability and aggression in male mice.

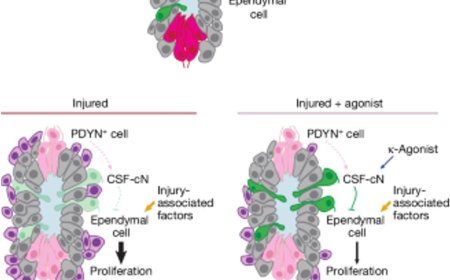

The researchers observed that in animals with the mutation, part of the population of vasopressin-releasing neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) was lost. In addition, they confirmed that these neurons release vasopressin in the lateral septum. As a result, little vasopressin reached the lateral septum. This alteration explains why the mutant mice showed reduced sociability and a marked decrease in defensive aggression, a behavior that, under normal conditions, allows males to defend their territory.

The study also shows that vasopressin acts in the lateral septum through two different receptors, each responsible for a specific aspect of behavior: receptor AVPR1a controls sociability, while receptor AVPR1b regulates social aggression. When the researchers manipulated these receptors, they were able to restore each behavior independently. “We managed to improve sociability without increasing aggression, which is fundamental if we are thinking about a future treatment”, explains the author.

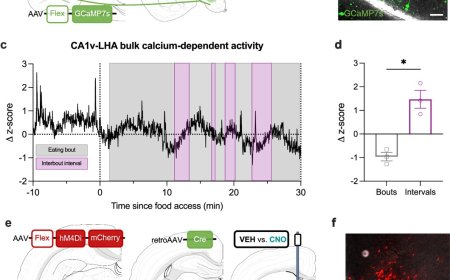

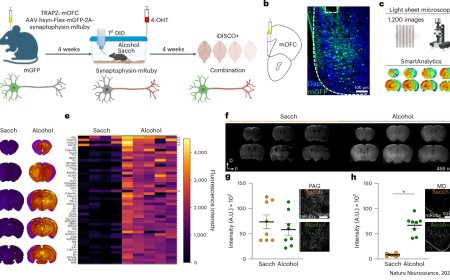

To achieve this, the team used a new vasopressin biosensor. This tool, never before applied to this hormone, made it possible to visualize in real time how vasopressin was released in the brain. “Thanks to this technology, we were able to demonstrate that the alteration was not present across the entire nervous system, but in a very specific circuit,” emphasizes the first author of the study.

The results of this research are protected by a patent application aimed at developing drugs capable of selectively activating the AVPR1a receptor, which is responsible for sociability. The goal is to design therapies that improve social deficits in people with autism without inducing side effects related to aggression.

The study was carried out in male mice because the vasopressin pathway is more developed in males, and only they display the territorial aggression under study. This sex difference could help explain, at least in part, why autism is more frequent in males, although it is also possible that in females the disorder manifests differently or is underdiagnosed. “Our results suggest that future treatments could be personalized, taking these differences into account,” adds the author.