Patient-specific human liver model to understand disease mechanisms

Liver disease is a major global health problem, causing over two million deaths worldwide each year. While animal models have helped to understand liver biology, they often fail to accurately translate to human biology. Due to the liver’s unique architecture, existing human models fail to replicate the complex interactions between different cell types in the liver and accurately show how diseases progress.

Existing tissue-derived liver organoid models consist of only one cell type and fail to replicate the complex cellular composition and tissue architecture, such as the liver periportal region. Complex 3D multicellular models that capture human liver portal cellular interactions do not exist for adult human liver tissue yet. This limits the ability to study liver disease and develop new treatments.

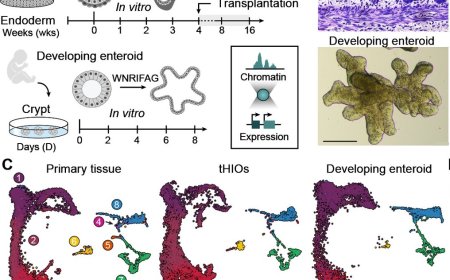

In the recent study, published in the journal Nature, researchers developed a patient-specific human periportal liver assembloid. This advanced liver model features adult human cholangiocytes, liver mesenchymal cells, and hepatocytes, which were derived from 28 patients. It contains multiple cells, which are combined together in a process similar to LEGO. Once assembled, the cells self-organize into 3D structures that reproduce in vitro the cellular arrangements and cell-cell interactions of the tissue in vivo.

One of the four lead authors says, “When we received the tissue from the patients, we first had to separate the individual cell types and expand them in a dish before combining them again.” The culture conditions were further optimized into what are now the final culture conditions to expand human hepatocytes.

Another lead author of the study continued the work by finding conditions to mature the cells in vitro. The author says, “I was able to develop the liver model further, so it featured bile canaliculi, which drain into the bile duct in the liver periportal region. When this bile drainage system is disrupted, it causes liver damage and disease. This is why it was so important for our liver models to include bile canaliculi. The present study is the first complex human liver model outside of the body that has bile canaliculi.”

Another lead author then worked on combining the cells to make the periportal assembloids. First, the author labeled the different cells (liver mesenchymal cells and cholangiocytes) in order to be able to track them once combined. Then, the right conditions were found to induce their self-assembly. “Additionally, I optimized the periportal assembloid protocol from the assembly method to the media that the cells were growing in. The proper medium is essential for promoting the cells' growth and differentiation,” says the author.

Another lead author of the study was mainly responsible for the molecular and functional characterization of the liver models. “I was looking at how well the models were performing their function. I tested how well our liver models function compared to normal human liver cells. With the help of computational biologist, I tested that the models correctly captured the gene expression of the living tissue.” With their existing liver models, the group created a living biobank of hepatocyte organoids from 28 patients, which can be frozen and thawed to reinitiate cultures when needed.

These patient-derived hepatocyte organoids sustained long-term expansion of hepatocytes in vitro and maintained patient-specific gene expression and bile canaliculus features and function of the in vivo tissue. After transplantation, expanded h-HepOrgs rescued the phenotype of a mouse model of liver disease.

By combining h-HepOrgs with portal mesenchyme and previously published cholangiocyte organoids4–6 , the researchers generated patient-specific periportal liver assembloids that retain the histological arrangement, gene expression and cell interactions of periportal liver tissue, with cholangiocytes and mesenchyme embedded in the hepatocyte parenchyma. They leveraged this platform to model aspects of biliary fibrosis.