What hinders DNA repair in patients with Huntington’s Disease

Researchers have discovered that the protein mutated in patients with Huntington’s Disease doesn't repair DNA as intended, impacting the ability of brain cells to heal themselves.

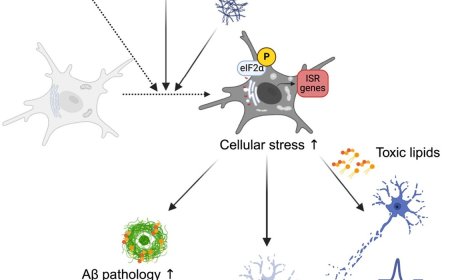

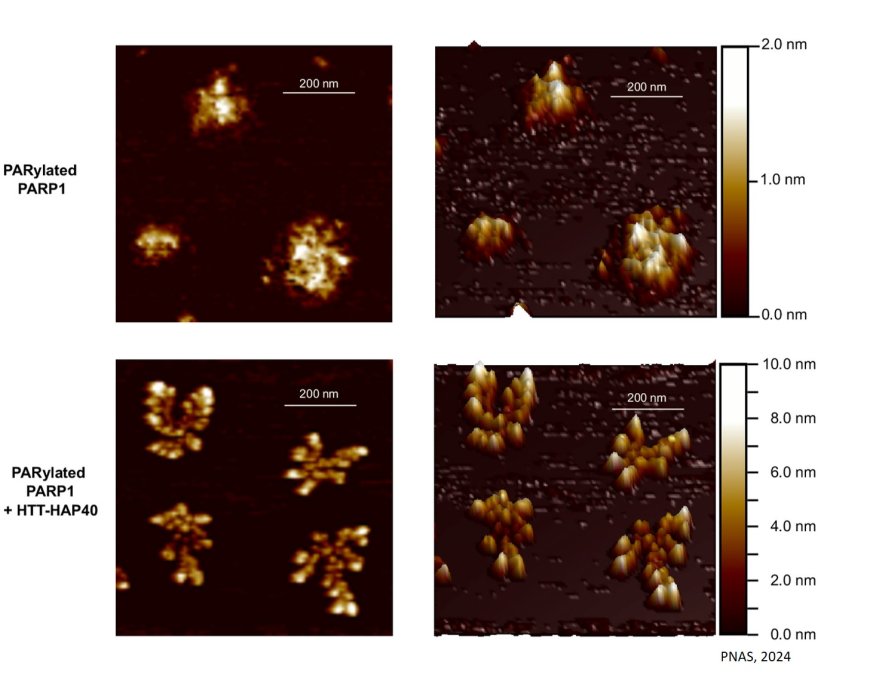

The research, published in PNAS, found that the huntingtin protein helps create special molecules that are important for fixing DNA damage. These molecules, known as Poly [ADP-ribose] (PAR), gather around damaged DNA and, like a net, pull in all the factors needed for the repair process.

In people with Huntington’s Disease, however, the research found that the mutated version of this protein doesn’t function properly and isn’t capable of stimulating PAR production, ultimately resulting in less effective DNA repair.

“We looked at the PAR levels in the spinal fluid from Huntington’s Disease patients and expected it would be higher due to the higher levels of DNA damage, but we actually found the opposite,” says the lead author. “The levels were quite a bit lower and not only in Huntington’s Disease samples, but also in people who carry the gene but aren't yet showing outward symptoms.”

This was an unexpected discovery because researchers have previously found PAR levels to be elevated in patients with other neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Huntington’s Disease is a genetic disorder that affects the brain and causes the gradual deterioration of nerve cells. For children of parents who have Huntington’s Disease, there’s a 50 per cent chance they will inherit the gene.

This discovery has a unique connection with cancer research. The senior author of the study says there are drugs that stop PAR production called PARP inhibitors that are used as cancer treatments.

The author says this may explain a long-standing observation that carriers of the Huntington’s Disease gene have significantly lower rates of cancer and may confer an evolutionary advantage in the human population, by avoiding early life cancer.

Researchers say future studies should look at different classes of FDA-approved PARP1 inhibitor drugs as they may hold promise not just for Huntington’s Disease but neurodegenerative diseases at large.