Brain networks work together for general intelligence!

Modern neuroscience understands the brain as a set of specialized systems. Aspects of brain function such as attention, perception, memory, language and thought have been mapped onto distinct brain networks, and each has been examined largely in isolation.

While this approach has yielded major advances, it has left unresolved one of the most basic facts about human cognition: its overall unity as an integrated system.

Now, researchers have conducted a neuroimaging study to investigate how the brain is organized and how that integrated system gives rise to intelligence.

“Neuroscience has been very successful at explaining what particular networks do, but much less successful at explaining how a single, coherent mind emerges from their interaction,” said the senior author.

Psychologists have long known that areas as diverse as attention, perception, memory and language are correlated, forming what they term “general intelligence.” This accounts for how humans function and adapt in a wide range of academic, professional, social and health contexts. It shapes how efficiently we learn, reason and perform in response to a multitude of everyday problems and tasks.

For more than a century, this structure has suggested that cognition is unified at a fundamental level. What has been missing is a theory to explain why such unity exists.

“The problem of intelligence is not one of functional localization,” said the senior author. “Contemporary research often asks where general intelligence originates in the brain — focusing primarily on a specific network of regions within the frontal and parietal cortex. But the more fundamental question is how intelligence emerges from the principles that govern global brain function — how distributed networks communicate and collectively process information.”

The research team investigated the predictions of the unifying framework, called the Network Neuroscience Theory. Their study was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

General intelligence is not itself a skill or strategy, the researchers argued. It is a pattern — the tendency for diverse abilities to be positively correlated. The study argues that this pattern reflects differences in how efficiently brain networks are organized and work together.

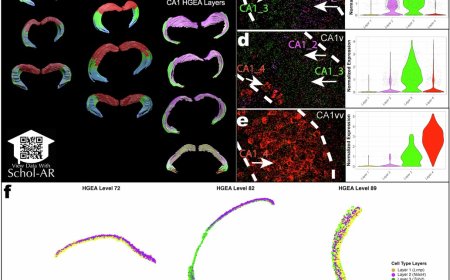

To test this claim, the cognitive neuroscientists analyzed brain imaging and cognitive data from one of the largest studies conducted to date, examining 831 adults in the Human Connectome Project, along with an independent sample of 145 adults. The researchers integrated measures of both brain structure and function to enable a more precise characterization of the human brain.

Rather than identifying intelligence with a particular cognitive function or brain network, the Network Neuroscience Theory characterizes it as a property of how the brain works as a whole. In this view, intelligence reflects how brain networks are coordinated and dynamically reconfigured to solve the diverse problems we encounter in life.

This research represents an important shift, according to the authors.

“We found evidence for system-wide coordination in the brain that is both robust and adaptable,” the lead author said. “This coordination does not carry out cognition itself, but determines the range of cognitive operations the system can support.”

“Within this framework, the brain is modeled as a network whose behavior is constrained by global properties such as efficiency, flexibility and integration,” the author said. “These properties are not tied to individual tasks or brain networks, but are characteristics of the system as a whole, shaping every cognitive operation without being reducible to any one of them.”

“Once the question shifts from where intelligence is to how the system is organized,” the author noted, “the empirical targets change.”

The researchers found evidence to support four predictions of the Network Neuroscience Theory.

First, the theory predicts that intelligence is not localized to a single brain network but arises from processing distributed across multiple networks. Intelligence, therefore, depends on how the brain manages the division of labor across different networks and combines them as needed.

Second, for the brain to manage this distributed processing, it requires integration and effective long-range communications. To synchronize those efforts, Barbey said, there is “a large and complex system of connections that serve as ‘shortcuts’ linking distant brain regions and integrating information across the networks.” These pathways connect structurally distant areas of the brain, enabling efficient communication and supporting coordinated processing across the system.

Third, effective integration requires regulatory control that coordinates interactions among networks by shaping how information flows throughout the brain. These areas serve as regulatory hubs, reaching out to other networks to orchestrate the brain’s ongoing activities. They selectively recruit the appropriate networks for the specific task at hand — whether it be piecing together subtle clues to make sense of a problem, learning a new skill or deciding whether a situation requires careful deliberation or a rapid, intuitive response.

Finally, the senior author said that general intelligence depends on the brain’s ability to balance local specialization with global integration. In other words, the brain functions best when tightly connected local clusters communicate well, but are still able to link to distant regions of the brain across short communication paths. This makes the most effective problem-solving possible, according to the co-authors.

The research suggests that intelligence is unified not because the brain relies on a single general-purpose processor, but because the same organizational principles shape how all cognitive functions work together.

Across both datasets, individual differences in general intelligence were consistently associated with these system-level properties. No single region or canonical “intelligence network” accounted for the effect.

“General intelligence becomes visible when cognition is coordinated,” the author noted, “when many processes must work together under system-level constraints.”

The implications of this study extend beyond intelligence research, the author added. By grounding cognition in large-scale organization, the study offers a principled account of why the mind is unified at all.

This framework helps explain why intelligence develops broadly during childhood, declines with aging and is particularly sensitive to diffuse brain injury. In each case, it is large-scale coordination — not isolated function — that changes.

The findings also inform ongoing debates about artificial intelligence and how AI models are developed. If general intelligence in humans arises from system-level organization rather than from a dedicated general-purpose mechanism, then achieving general intelligence in artificial systems may require more than the accumulation or scaling of specialized capabilities.

“This research can push us into thinking about how to use design characteristics of the human brain to motivate advances in human-centered, biologically inspired artificial intelligence,” the senior author said.

“Many AI systems can perform specific tasks very well, but they still struggle to apply what they know across different situations.” The author said. “Human intelligence is defined by this flexibility — and it reflects the unique organization of the human brain.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-026-68698-5

https://sciencemission.com/network-architecture-of-general-intelligence-i