Cellular mechano-sensation linked to gene enhancers!

Researchers used CRISPR technologies to discover previously unannotated stretches of DNA in the ‘dark genome’ that are responsible for controlling how cells sense and respond to the mechanical properties of their local environment.

Understanding how these DNA sequences affect cellular identity and function could give researchers new therapeutic targets for illnesses that involve changes to mechanical properties of tissues, including fibrosis, cancer and stroke, as well as long-term issues such as neurodegeneration and even aging.

This work appears in the journal Science.

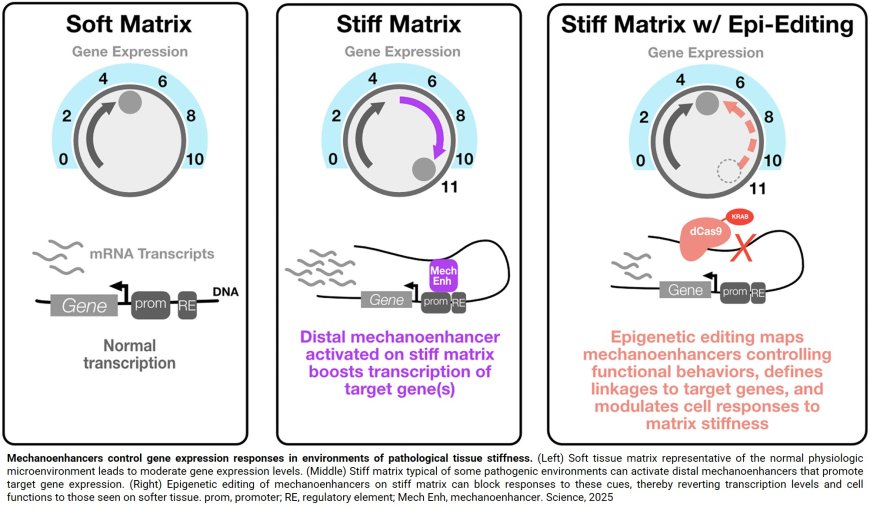

The local environment around a cell plays a critical role in determining how that cell functions and the characteristics it develops within different tissues. Advances in epigenetic profiling and CRISPR-based screening tools have enabled researchers to explore how chemical stimuli like hormones, signaling proteins like cytokines, and even pharmacologic medications can shape gene expression. But how mechanical structure, such as tissue stiffness or applied external forces, affects cellular function is not fully understood.

“Mechanical stimuli from a cell’s microenvironment are also potent regulators of many fundamental cell processes, including growth, death, differentiation and migration,” said the senior author. “We know these physical stimuli play key roles in tissue development, regeneration, aging, and disease pathology such as fibrosis and tumor formation, but the precise mechanism through which they act has been difficult to understand.”

The team has spent over a decade developing techniques to use CRISPR to modulate epigenetic activity, which controls how much of our genes are produced. Originally discovered as a bacterial defense system against viruses, CRISPR targets very specific DNA sequences. While the original system carries a protein called Cas9 that slices the targeted viral genomes, the DNA-targeting part of the system can operate independently. One of the methods the team has pioneered involves using a version of CRISPR-Cas9 to explore and modulate genes without cutting them. Instead, it makes changes to the structures that package and store DNA, affecting the activity level of the accompanying genes.

“Only 1-2% of our genome encodes for genes. The other 98% of the genome clearly plays an important role in shaping cell identity, response to the environment, and susceptibility to disease, but until recently we didn’t have the tools to probe the function of this ‘dark’ part of our genome,” said the author. “A significant function of the dark genome is to act as ‘enhancers’ of genes – dialing them up and down in different situations. But it’s largely unknown where the enhancers are in our DNA sequence, which genes they are controlling, and how that relates to cell-environment interactions”.

To understand how cells sense their mechanical environment, the team partnered with an expert in mechanobiology and made hydrogels that mimic tissues of different stiffness and cultured cells on these gels. The researchers then used sequencing tools to quantify RNA levels and map regions of open chromatin, or accessible DNA, in order to determine changes to gene expression and genome structure in each sample.

“In just 20 hours on the different gels, we observed changes in the levels of thousands of genes and the structure of almost fifty thousand regions of the genome,” shared another author. “This underscores the profound effect of the mechanical microenvironment on cell biology and clarifies how changes in tissue structure can play a significant role in diseases like fibrosis and cancer.”

It was more challenging to determine which changes in the ‘dark’ genome affect cell function by acting as enhancers of specific genes. For this, the team used CRISPR to silence the activity each region of DNA and determined the resulting effects on cell growth and migration. The regions that showed strong functional effects were further profiled by measuring the levels of every gene in response to blocking these enhancers with CRISPR. The regions that changed structure in response to local mechanical properties, altered cell growth and/or migration, and controlled the levels of specific genes were dubbed ‘mechanoenhancers’ to reflect their role in regulating cell response to environment.

To better understand the function of mechanoenhancers and their role in disease, they teamed up with an expert in methods for analyzing the physical interactions of enhancers and genes, and showed that mechanical environment in fact alters the contact of mechanoenhancers to their gene targets. Using the samples from lung biopsies that showed activity of mechanoenhancers controlling disease-related genes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

“Mapping these mechanoenhancers can improve our mechanistic understanding of diseases that involve changes to tissue mechanical properties, like fibrosis and cancer, and possibly lead to new drug targets or methods for engineering how cells sense pathologic mechanical environments,” said another author.