A nucleosome switch primes hepatitis B virus infection

In their effort to answer a decades-old biological question about how the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is able to establish infection of liver cells, new research has identified a vulnerability that opens the door to new treatments.

The team successfully disrupted the virus’s ability to infect human liver cells in the laboratory using a compound already in clinical trials against cancer — laying the groundwork for animal model studies and potential drug development based on their insights, according to findings published in Cell, a top life sciences journal.

Hepatitis B is a liver infection that affects almost 5% of the world’s population. It causes long-term damage to liver cells and is one of the leading causes of liver cancer.

At the heart of the mystery that intrigued the researchers lies a key viral gene that encodes for a protein called X. This protein is essential for HBV to establish a productive infection in host cells and the expression of its viral genes. However, the X gene itself is encoded within the viral genome.

“This raises a classic chicken-and-egg question that has puzzled scientists for decades,” the author says. “How does the virus produce enough X protein to drive viral gene expression and establish infection?”

Furthermore, the gene that encodes protein X is considered the virus’s oncogene — that is, the gene responsible for the disease’s progression toward cancer, the author adds. That’s because protein X degrades proteins in the host that are involved with DNA repair. Not only does this keep the host from silencing protein X’s activity, but the infected cells are also more likely to accumulate DNA errors that build up over the years and decades, leading to the development of cancer.

“One of the main challenges with treating hepatitis B is that the existing treatments can stop the virus from making new copies of itself, but they don’t fully clear the virus from infected cells, allowing the virus to persist in the liver and maintain chronic infection,” says another author.

The hepatitis B vaccine is also effective, but maintaining immunity often requires booster shots. Moreover, it doesn’t help people who are already infected. This happens, for example, due to transmission of the virus from mother to child, which is very common in developing countries. Access to vaccines and treatment is also more limited in some parts of Africa and Asia, where rates of infection are higher.

Digging into the mystery of protein X was a challenge, explains the author. The existing tools weren’t capable of shedding light on what was happening in those critical early hours of an infection.

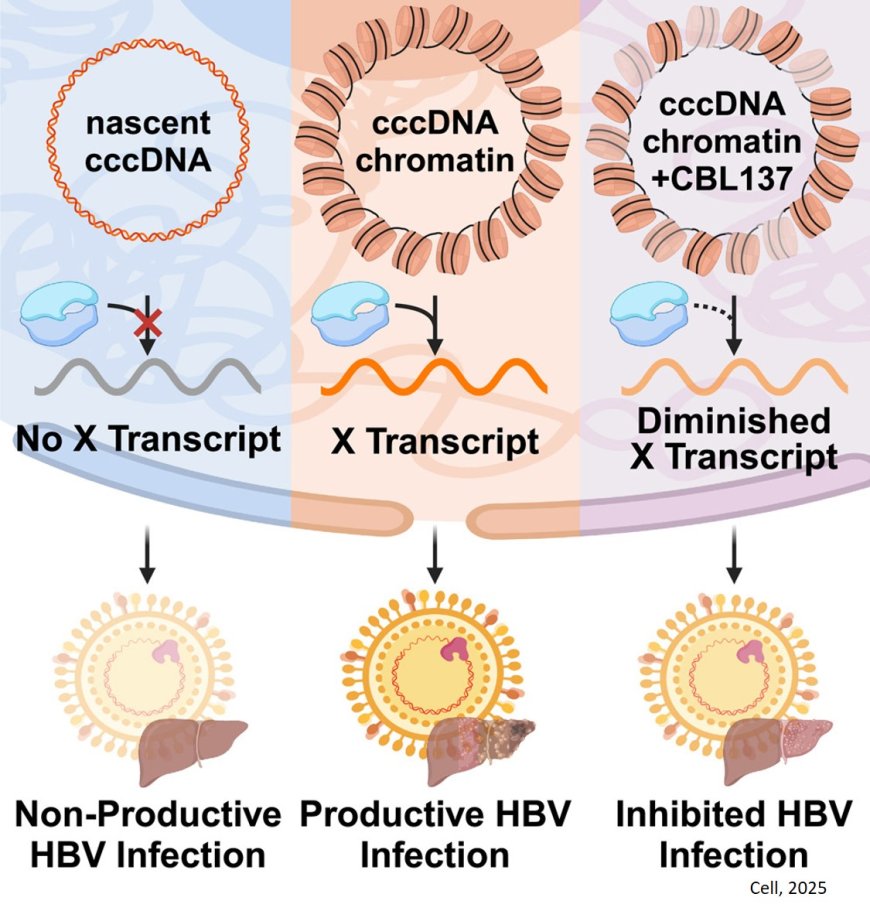

The research team determined that in order for protein X to get made, the hepatitis B virus’s DNA needs to get organized into DNA-histone complexes called “nucleosomes.” Nucleosomes are like beads on a string — the string is the viral DNA, and the beads are host-provided histone proteins, around which DNA gets wrapped; nucleosomes are the building blocks of chromatin, the material that makes up chromosomes.

“Conventional wisdom says that packaging a gene’s DNA into nucleosomes would block or slow down the cell’s ability to read out that gene to make functional proteins, like protein X,” another author says. “But in complex organisms like humans and in the viruses that infect us, gene regulation is not always so straightforward. The presence and the positioning of nucleosomes on DNA can be important in directing cellular mechanisms to transcribe some genes. We found that to be the case for the HBV gene encoding protein X — the presence of nucleosomes on the viral genome is necessary for the transcription of RNA that gives rise to functional protein X.”

This discovery opens the door to understanding how the X gene is regulated and how HBV infection is established. Moreover, the researchers were elated to discover a potential therapeutic opportunity: If one could disrupt the formation of these chromatin structures, then one could disrupt the virus’s ability to start and maintain an infection.

The team tested five small-molecule compounds known to impair chromatin formation. Only one blocked the production of protein X in liver cells: an anticancer drug candidate called CBL137.

Importantly, it worked at very low concentrations — many times smaller than participants in clinical trials for cancer were receiving, and using doses that only affected the virus, but not human cells.

“This made us very optimistic about the possibility of developing a treatment approach while preventing or limiting side effects,” the author says.

“Moreover, if these results are confirmed through additional study, we are optimistic the approach could be used to treat chronic infections for the first time — and therefore could represent a potential cure,” the author adds.

Additionally, CBL137 might prove similarly useful to target or study other chromatinized DNA viruses like herpesviruses and papillomaviruses, the researchers note.

To further develop the team’s research toward a potential clinical trial, the next step would be to study the safety and effectiveness of CBL137 in animal models — though these are limited due to the narrow range of species HBV can infect, the researchers say.