How a tick-borne virus enters human cells

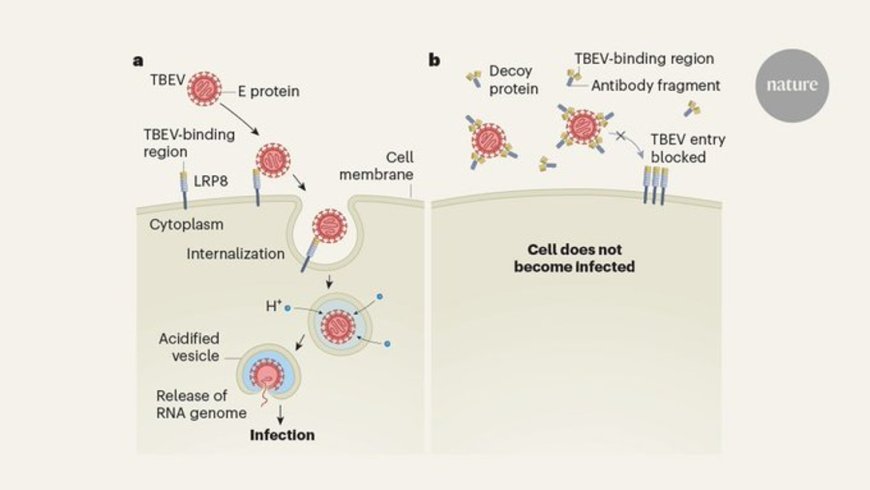

The protein on human cells that tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) uses for infection has now been identified—a major step toward understanding how TBEV causes neurological disease and for developing antiviral drugs. The study was published in the journal Nature.

TBEV is one of many mosquito- and tick-borne flaviviruses responsible for serious diseases, which also include dengue virus, yellow fever virus, Zika virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus. “But until now, scientists have been unable to identify essential host-cell protein receptors for any flavivirus,” said study co-leader. “By conclusively demonstrating that TBEV requires a critical protein receptor to infect human cells, we open the field to discovering receptors for other flaviviruses and devising therapies for the devastating infections they cause.”

TBEV is carried by ticks that usually transmit the disease to humans through bites. The virus can infect the brain and spinal cord, causing severe and sometimes life-threatening disease. TBEV is endemic throughout Northern, Central and Eastern Europe, and Central and East Asia, where it causes more than 10,000 clinical cases a year, some of them fatal.

“The number of cases caused by TBEV is likely to grow as the geographic range of the tick that spreads the infection continues to move into new areas,” said a research assistant professor. “Several TBEV vaccines have been approved, but access to them is limited, especially in low-and middle-income countries in the endemic zone, and there are no specific treatments for people already infected with TBEV.”

In seeking the receptor that TBEV “unlocks” to gain entry to human cells, the research team suspected that a cell protein was being targeted. Using a human cell line, they amassed a “library” of thousands of cell variants in which a different gene had been deleted; the variants were then exposed to TBEV. Only cell types lacking a gene necessary for TBEV infection should survive virus exposure.

As expected, this “Survivor-like” competition implicated a number of genes that might be important for viral infection, most of which had been found previously for other flaviviruses. “What really stood out in our screen was the gene for LRP8, a low-density lipoprotein receptor located on the surface of cells,” said another author. LRP8 is highly expressed in the brain and at the blood-brain barrier and plays special roles in neurological development and function. The team showed that LRP8 is specifically recognized by TBEV’s envelope protein E, known to play crucial roles in host cell entry, immune evasion, and viral spread. “LRP8 appeared to be the long-sought cell-surface protein to which TBEV must bind in order to enter and infect human cells, including key cell types in the brain such as neurons,” said the author.

In a key follow-up experiment, members of the team determined that LRP8 is important for TBEV infection in living organisms—mice, in this case. They treated mice with a “decoy receptor” that prevents TBEV from binding to LRP8 on cells. They then exposed the mice to a highly virulent strain of TBEV. Nineteen of the 20 animals treated with the decoy receptor did not develop any clinical signs of infection. By contrast, all untreated mice rapidly developed severe disease and succumbed to infection. “It was really exciting to see that LRP8 is crucial for TBEV to efficiently infect the brain,” the author said.

“We need to perform further laboratory and animal studies to understand exactly how LRP8 allows TBEV to infect people and cause neurological disease,” the author said and added that “it would also be fascinating to learn whether the virus uses similar proteins to colonize ticks, which are part of the viruses’ natural life cycle and transmit the virus to people.”

“More research is needed, but this is a promising start toward developing new measures for preventing and treating flavivirus infections,” added the author.