Paternal dietary macronutrient balance and energy intake drive metabolic and behavioral differences among offspring

New research, published in Nature Communications, finds that the macronutrient balance in the diet of male mice affects the level of anxiety-like behaviour of sons and the metabolic health of daughters.

The research provides a step towards understanding how the effect of diet can transmit from one generation to the next via a father’s sperm. It could ultimately inform dietary guidelines for fathers-to-be, with the goal of lowering the risk of metabolic disease and mood disorders in the next generation.

Parents like to believe they can shape the interests and behaviour of their children, with mixed success. But a new study from an international team of researchers confirms this is the case for mice, with father’s shaping their offspring’s health through their own diet.

Scientists have already discovered that a mouse father’s diet can have an impact not only on his own reproductive health but on that of his offspring. Over- or under-feeding male mice can affect their offspring’s metabolism and behaviour, as well as their risk of cancer. What is less understood is whether there are diverse types of health impacts on the health of offspring, depending on the type and composition of the diet of male mice before conception.

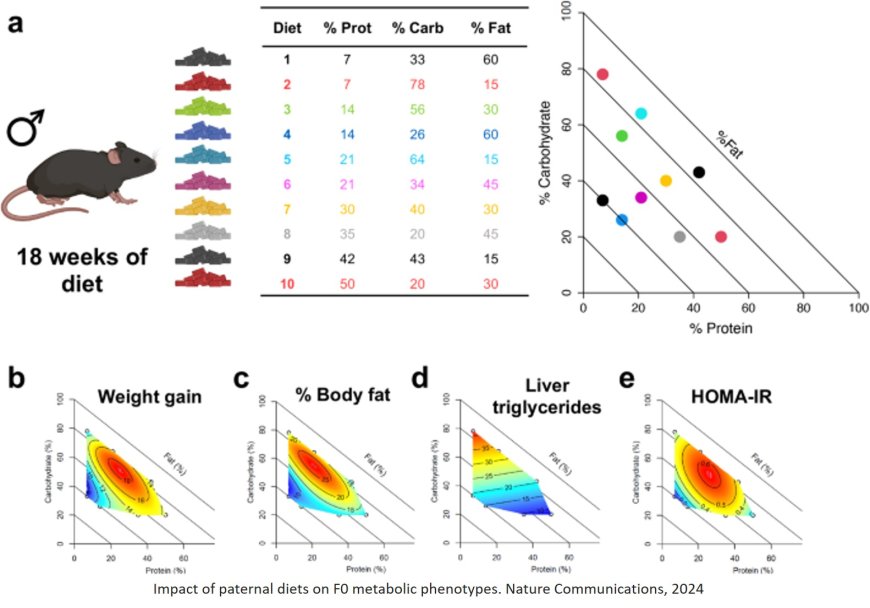

Researchers fed male mice one of ten diets differing in the proportions of protein, fats, and carbohydrates, then allowed them to mate with females reared on standard diet. The behaviour and physiology of the resulting pups were then studied.

The scientists discovered that male mice fed low protein and high carbohydrate diets were more likely to have male offspring with higher levels of anxiety, as measured by time spent in the safety zones of their maze. They also found that male mice that were fed high fat diets were more likely to have daughters with higher levels of body fat and markers of metabolic disease.

“Our study shows that the type of diet eaten before conception can program specific characteristics of the next generation,” says the co-senior author.

“It is extraordinary that by titrating mixtures of protein, fat and carbs in the father’s diet we could influence specific features of his sons and daughters health and behaviour. There is some important biology at play here,” said another co-senior author.

The team also observed that males on a low protein diet also ate more food overall. However, thanks to the study design, they could determine that both the amount of calories, and the macronutrient composition of the males’ diets, influenced the health of their offspring.

“Our study shows that it’s not just eating too much or too little, but the composition of the diet that can have an impact on future children,” says another author.